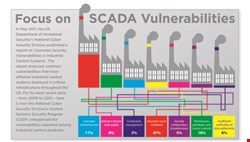

Threats to aging supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, which monitor and control key industrial processes in critical infrastructure, have been growing in recent years. The latest threat comes from the Flame malware that has been infecting SCADA systems for years – undetected.

The most notorious attack against a SCADA system, however, was the Stuxnet worm that infiltrated the nuclear fuel enrichment facility at Iran’s Natanz plant in 2010 and significantly disrupted its centrifuges. Stuxnet was a leap forward for malware targeting SCADA systems says Dale Peterson, chief executive of Digital Bond, a control system security consulting firm.

“The whole purpose of Stuxnet was to change the programming of the PLC [programmable logic controller] so that the physical process operated differently”, Peterson tells Infosecurity. “Stuxnet made the centrifuges spin faster than they were supposed to. But it also reported back that they were operating exactly as they should….Before it made the centrifuges spin faster, it recorded the data and replayed the good data back to the operator”, he explains.

Flame and Duqu, by contrast, do none of those things, Peterson says. “They are not designed to attack an industrial control system; they are designed to gather information.”

SCADA systems have a number of vulnerabilities, Peterson relays. Crucially, they were not originally designed to connect to networks. Now that many of them are connected, the majority do not have basic security in place, such as authentication.

“If I send a command to start or stop something, there is no authentication on that command….The system on the other end just does what it is told without any thought to who is telling it to do that”, Peterson says. “The connection [of the SCADA system] to other networks exposes this vulnerability.”

New World, Old Technology

Parveen Jain, chief executive officer of RedSeal Networks, agrees with Peterson, noting that cybersecurity concerns began when SCADA systems – many of which were developed 25 to 35 years ago – were connected to networks and ultimately the internet. There was no concern about internet security when these systems were first developed, recalls Jain, who worked on SCADA systems for the nuclear industry back in the mid-1980s.

“We would code in Fortran, and we focused on ensuring the SCADA system delivered what was supposed to be delivered in terms of monitoring and supervising the controls….In the last 10 or 15 years, these systems have become more vulnerable”, he warns. “The problem is that because the code is so old in these SCADA systems, I don’t think anyone has a real handle on how many or what types of vulnerabilities exist.”

Peterson noted that Digital Bond’s Project Basecamp research effort has exposed a number of significant vulnerabilities in PLCs – which are SCADA components that provide on-site process control – manufactured by General Electric, Rockwell, Schneider, and other major vendors.

“They were embarrassingly easy to compromise”, he says. “It was pretty trivial to cause serious damage. And this is 10 years after 9/11. They should know better.”

Project Basecamp provided the results of the testing to the manufacturers, but most of them did not respond. “They have gone years without having to fix these problems. Some of them think they can go another 10 years without fixing anything”, Peterson laments.

It Ain’t Just a River in Egypt

The critical infrastructure industries are in denial about the extent of their cyber vulnerabilities and the need to take urgent efforts to remedy them, says Stephen Flynn, co-director of Northeastern University’s George J. Kostas Research Institute for Homeland Security in Burlington, Mass.

“We are in a transition phase where these sectors are ignorant or in denial about the security problems”, Flynn tells Infosecurity.

“The cyber risk is now so pervasive that everybody should be taking steps to manage the risk…Any determined adversary can get access to this information and become skilled at it with just what is available right now”, Flynn warns.

“What has happened over the last decade is that these systems have been upgraded using commonly available software”, he says. “They have moved onto the network and internet and become accessible remotely by attackers who want to cause mischief.”

Flynn cautions that toolkits for the purpose of attacking SCADA systems are being circulated among hacker groups. “You can get onto these systems if you are motivated and follow protocols that are being widely shared among the hacker community”, he says.

| "[Flame and Duqu] are not designed to attack an industrial control system; they are designed to gather information" |

| Dale Peterson, Digital Bond |

“The basic risk is that these systems control the operations of industrial systems, and critical infrastructure”, Flynn notes. “If the systems are compromised and, more importantly, commandeered…then you can direct the infrastructure to do things that can be highly disruptive.”

Because of these vulnerabilities, Flynn advises that attackers could take control of a hydroelectric dam and instruct the dam to open up and flood those who live downstream. Alternatively, hackers could send signals to a substation on the electric grid to overwork itself and destroy key components, resulting in power outages that could last weeks or months. Finally, they could gain access to SCADA systems running water treatment plants and change the mixture of chemicals that treat the water, producing water that is harmful – or even deadly – to drink.

“The bottom line is that compromise of the SCADA systems can lead to mass destruction and loss of life. These systems can turn on the society they are supporting”, Flynn implores.

Run-of-the-Mill Malware

While flashy malware like Stuxnet gets a lot of press, most of the incidents with industrial control systems involve standard malware that finds its way into the system and causes less-than-catastrophic problems, Digital Bond’s Peterson explains.

Olli-Pekka Niemi, head of the Stonesoft vulnerability analysis team, agrees. SCADA systems, Niemi advises, often use widely available software and operating systems, such as Windows and UNIX, and are vulnerable to the same threats encountered by other users of these systems.

Everyday threats, such as gaps in security infrastructure and denial-of-service attacks, pose a far greater risk to SCADA security than the highly publicized attacks, Niemi judges.

“Exploitable vulnerabilities on [SCADA systems] are being found constantly. These vulnerabilities often remain unpatched in private networks. The reason may be that third-party software prevents patching, or that patching requires downtime for the SCADA-controlled processes, or that the patching requires network access to vendors to update servers”, he explains.

The traditional SCADA security model based on isolated networks – what Niemi describes as the industry cliché of “security through obscurity” – has been “totally” compromised in his estimation.

“Isolated networks are not really that isolated; instead, there are usually all kinds of connectivity that can be exploited”, he observes. “At worst, the systems are actually connected to the internet. And even if the networks are isolated from the internet, malware may have compromised them through removable media, such as USB sticks or infected laptops and other mobile devices.”

Plugging the Gaps

To protect themselves, organizations should “identify all connections to SCADA systems/networks, and then everything that is not needed should be cut off”, Niemi advises.

“For the remaining connections, strong authentication, encryption, and intrusion detection and protection systems should be deployed. Operating system and application security patches should be installed on a regular basis. Every organization should also have a carefully thought incident response plan, because incidents happen”, he adds.

Niemi recommends that organizations also deploy advanced evasion technique detection capabilities and traffic normalization, which enables the intrusion protection system to detect malicious code hidden in the data flow.

| "Isolated networks are not really that isolated; instead, there are usually all kinds of connectivity that can be exploited" |

| Olli-Pekka Niemi, Stonesoft |

Peterson explains that the most important considerations for SCADA systems are integrity and availability. “The most basic thing is that commands that can do damage need to be authenticated – the source and the data. Also, these systems need to go through a software development lifecycle” in which software security bugs are uncovered and fixed, he says.

“These systems are fragile, easy to crash and compromise, because the software development teams haven’t integrated security into their development”, Peterson observes. The fix does not involve new technology, just applying existing technology to these systems, he concludes.

RedSeal’s Jain notes that the critical infrastructure industry is “trying to create a wall around their SCADA systems so that they control the access to these systems. Once they control the access to these systems, then they know they can manage the security of those systems. But creating this wall is not an easy task because of the vastness and complexity.”

Jain recommends that organizations use standard networking and security devices around the infrastructure, such as application-level firewalls and intrusion prevention systems, and set up a multilayer defense.

“These are complex and evolving networks. So even when organizations have deployed these security devices, they need to be able to measure their level of defense on an ongoing basis”, Jain stresses.

“All of these systems have redundancies and backup systems. So the guys that want to exploit SCADA systems have to be very sophisticated”, he continues. “If there is a silver lining to all this, we developed these systems to take care of emergencies on a routine basis.”

So what does the future hold for SCADA system security? Western governments and industry received a wake up call from the success of Stuxnet, but the problems with these systems lie deeper, in their origins and the attitudes of vendors. The good news is that the fixes are readily available. The bad news is they are not being deployed fast enough to prevent a catastrophe.