Cloud-native threats continue to be one of the fastest growing trends of 2020. In my previous blog post I discussed GuLoader as an example - an evasive malware downloader abusing familiar cloud services like Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive to retrieve the malicious payload. This downloader is growing in popularity to the extent that, up to 25% of all packed samples are now GuLoaders.

Ironically, the same report has also exposed CloudEye, an Italian company providing a front-end cover for Guloader.

This downloader is extremely flexible and evasive, making it suitable to distribute multiple payloads. GuLoader continues to be the preferred choice for cyber-criminals and has been used successfully in several recent campaigns, both targeted and opportunistic. Examples include NetWire and Nanocore Remote Access Tools, Hackbit ransomware (used as part of a targeted operation against mid-level employees across Austria, Switzerland and Germany), and a keylogger named “Mass Logger” – all of which demonstrate the wide spectrum of how this downloader can be used.

As well as distributing malware, cloud services are increasingly used to host phishing pages. This technique, called cloudphishing, has evolved considerably in the advent of COVID-19. The malicious actors are getting more and more creative and are launching campaigns with different levels of sophistication which are able to exploit cloud at multiple stages of the kill chain, creating a dangerous liaison among different cloud services.

According to the Q1 2020 Phishing Trends Report issued by the Anti Phishing Working Group, webmail and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) continue to be the most targeted phishing services, increasing to 33.5% from 30.8% in Q4 2019. This is, in part, is a consequence of the new landscape in which we operate, that has seen an exponential increase in remote working and, a corresponding growth in the adoption of cloud services (without proper end user training or education).

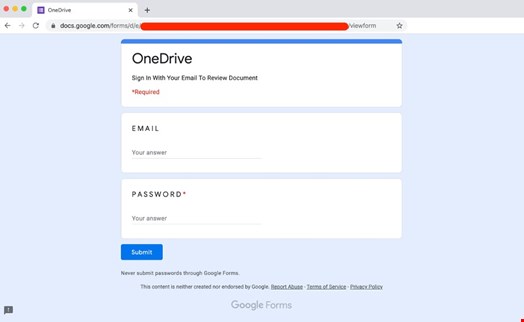

Unsurprisingly, cyber-criminals have quickly discovered ways to capitalize on this trend with some quite bizarre and paradoxical attack scenarios. This picture shows a very simple, rogue Microsoft OneDrive login page hosted on Google Forms - a “liaison dangereuse” between two of the most common and familiar cloud services.

Despite the layout being completely different from the Microsoft style, the Google logo is clearly visible on the page and, as if that’s not enough, the form says to “never submit passwords”. Similar attacks are increasingly common, and successful.

One of the advantages of the exploitation of cloud services for malicious purposes is the simplified hosting: signing up for a Google account and creating similar phishing pages only takes a few seconds and if those pages are taken down, they can be restored quickly.

As a consequence, a similar attack scenario is ideal for massive opportunistic campaigns where the bad actors rely more on the size (the number of malicious emails sent) rather than on the quality (the layout of the phishing page).

Variants of similar attacks exist for multiple cloud services (such as Microsoft Forms or Microsoft Excel Online) where the same techniques - the simplified layout and the useless warning to never give out the password - are clearly visible. Unfortunately, if users ignore the warning signs and submit their passwords the consequences for the victims are the same.

Avoid being “cloudphished”

Attacks are becoming more frequent and successful - not only because of their relative simplicity, but also because they exploit an important aspect: the implicit trust in legitimate cloud service providers. From a technological standpoint, platforms like Dropbox, Google Drive or Microsoft OneDrive are considered inherently safe within an organization and aren’t adequately inspected.

Moreover, the need to inspect cloud traffic, which now accounts for 85% of the web enterprise traffic, is often inhibited by the limitations and shortcomings of legacy on-prem web security gateways, for example in terms of performing SSL decryption at scale.

The same implicit trust is dangerous for users who feel safe when presented with a familiar logo on the login page. This trust leads them to ignore the misplaced details such as the slightly different layout, or the fact that the login page is hosted on a completely different, albeit trusted, cloud service.

Educating users to spot misplaced detail is always good practice, especially in difficult circumstances like we are experiencing today, when the workforce went remote almost overnight, with many workers shifting to an unfamiliar environment.

The growing adoption (and exploitation) of cloud services requires a cloud-native security approach that is able to enforce security controls on encrypted traffic such as threat protection and DLP, without any service being implicitly trusted.