As the Allied cryptanalysis center during World War II, Bletchley Park was the site of the first industrial scale code-breaking effort, enabled by the pioneering work of luminaries like Alan Turing, Tommy Flowers and William Tutte.

During the war, Bletchley Park was a sprawling collection of old buildings and temporary huts, housing the various branches of Station X, including cryptanalysts assigned to breaking Enigma codes used by German troops, and analysts working on the Lorenz cipher used by the German high command. After the war, Bletchley Park was used by a variety of tenants, including GCHQ and British Telecom.

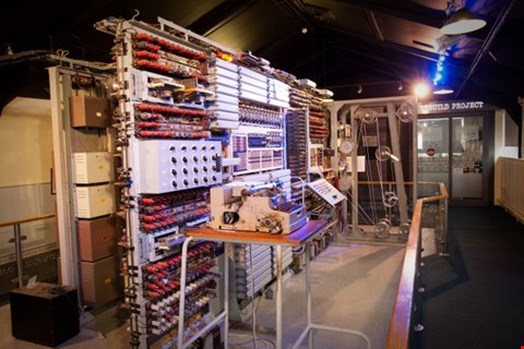

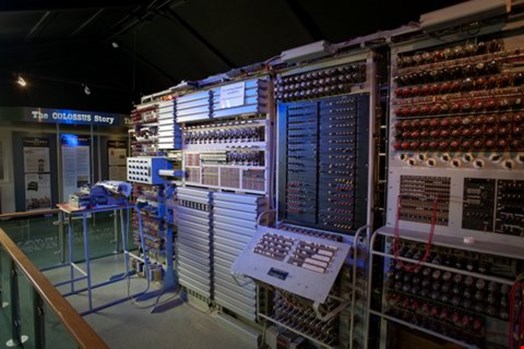

Campaigns for the Park’s preservation started with volunteers in 1991. Their centerpieces were the industrial scale decryption machines at Bletchley Park: the Turing Bombe for the Enigma code, and the Colossus computer for the Lorenz cipher.

When I first visited Bletchley Park in 2009, the site and its exhibitions were under enormous pressure financially. Several times, the Park was close to being closed and demolished; it took until 2010 until it could finally be considered ‘saved’.

Today, Bletchley Park has largely been restored, and houses two world class exhibitions. The first is operated by the Bletchley Park Trust, focusing on the history of code breaking during World War II, a story that ends in 1945 with the Colossus computer. The other is the National Museum of Computing (TNMOC), showing the next chapters of the story, with the same Colossus machines as the starting point for the development of digital computing over the next seven decades.

Colossus and The National Museum of Computing

Block H at Bletchley Park, now occupied by The National Museum of Computing (TNMOC), had originally been home to six Colossus computers. After the war, the Colossi were dismantled for parts and scrap metal.

The project to build a reconstruction of a Colossus began in 1994 based on the few remaining documents not destroyed after the war with the help of former Colossus engineers. The driver behind the reconstruction was Tony Sale, a computer engineer later to become museum director at the Bletchley Park Trust.

In 1996, Kevin Murrell, a software business owner, visited a small computer exhibition at Bletchley Park and met Tony. A self-described hardware geek, he was visiting in response to an appeal for a hardware expert for repairs on a PDP11.

At the time he didn’t know much about Bletchley Park, but he quickly became intrigued. He fixed the PDP11 on his first Saturday and then spent every Saturday for almost a decade working on the restoration of a growing collection of legacy hardware. His experience and skill as an entrepreneur also helped him support the administrative side of things. “I was used to dealing with lawyers and accountants,” he says.

Kevin helped establish TNMOC as a charity and the Trust took over the lease of Block H, where the Colossus rebuild stood. Today, TNMOC has a team of 60 volunteers and six paid staff.

Kevin describes TNMOC’s staff as “enthusiastic for running machines and explaining how we got to this point in our history.” He adds that, like himself, many volunteers have successful careers, and they view holding a soldering iron as relaxation. They come from all walks of life, and like the visitors, some come with a keen technical interest and highly detailed questions; others are interested in the bigger picture.

The Future of TNMOC

TNMOC hosts the only working Colossus reconstruction. However, it displays working machines from every decade, including the world’s oldest original working digital computer (the Harwell Dekatron, also known as WITCH), mainframes from the 1970s, desktops of the 1980s, right up to the handhelds of today.

The confined space of the historic Block H means TNMOC is not able to show all of its treasure trove. But Colossus irrevocably ties TNMOC to Bletchley Park, so moving it elsewhere would require leaving Colossus behind, or moving it out of its historically appropriate location.

Kevin says he hopes to grow the number of visitors, given the pervasiveness of modern computing. He is equally proud of the success the museum has had with its exhibitions and its courses for schools. These courses are booked to capacity, providing a hands-on way to learn programming.

Anything in today’s computing world, says Kevin, is here for a reason, and it can usually be traced back. In many cases, when you follow it long enough, that trace leads back to Colossus, here at Bletchley Park.

References and further reading:

- http://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/content/about/bpsite.rhtm

- http://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/magazine-features/preserving-bletchley-park/

- http://www.savingbletchleypark.org/

- http://www.tnmoc.org/special-projects/colossus-rebuild

- http://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/resources/filer.rhtm/683075/chapter+8.9+-+block+h.pdf

- http://www.tnmoc.org/news/news-releases/tony-sale-1931-2011

- http://www.theregister.co.uk/2012/11/21/harwell_dekatron_reboot/

- http://www.tnmoc.org/