When Hippocrates wrote his famous oath – which all medical practitioners must swear to – he used papyrus, rather than a word processor. But one of the clauses remains as true today as it was back then.

“What I may see or hear in the course of the treatment or even outside of the treatment in regard to the life of men, which on no account one must spread abroad, I will keep to myself holding such things shameful to be spoken about”, he said. In other words, keep medical records secret.

Hippocrates would probably utter more than a few oaths today, if he had the misfortune to meet modern healthcare administrators. They’re losing patient data by the bucketload, according to experts.

Ponemon’s ‘Second Annual Benchmark Study on Patient Privacy & Data Security’, published in December 2011, found that the frequency of data breaches in the US healthcare sector had risen by a third in comparison to the previous year. Ninety-six percent of all healthcare providers reported at least one breach in the last two years.

Since the compliance date with the HIPAA Privacy Rule, enacted in April 2003, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has received over 72,684 complaints concerning health information privacy.

Paradoxically, part of the problem could be awareness. “We’re paying more attention to it, which means we’re going to see more of it”, says Denise Anthony, a faculty affiliate with the Center for Health Policy Research at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. “But it isn’t very organized either”, she adds.

A Fragmented System

This lack of organization is hardwired into the system, says Anthony: “The fractured and fragmented healthcare system means that there are many different entities that touch your data when you’re getting healthcare. That means there’s a lot of information moving around.”

The US healthcare system is a for-profit variation of the Bismarck model. Under this system, insurance payments made by employers and employees finance ‘sickness funds’ that are drawn on by healthcare providers. The various players in this value chain – such as insurance companies, clinics, general practitioners, non-profit governmental Medicaid organizations, pharmacies, and hospitals – all have to see the patient’s data.

“There are all kinds of third parties involved too. There are billing agencies and companies that do the billing for lots of providers. There are transcription services”, Anthony says. “The pharmaceuticals are their own industry, with different kinds of third parties that exchange information back and forth.” Every data transfer point represents a potential breach point.

Private practices were the type of healthcare facility most commonly asked to amend their operations to be compliant with security rules, according to the HHS. General hospitals were the next most frequent transgressors, followed by outpatient facilities, health plans (including health insurance issuers), and pharmacies.

These breaches can span various types. “We get breaches about mobile devices that are unencrypted, although we are getting fewer of those”, says Dawn Monaghan, strategic liaison group manager for public services at the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office. “We’re now getting the majority of breach reports around the decommissioning of data.”

This often happens when a health organization subcontracts decommissioning to a data processing firm without proper checks. “A primary care trust will send 245 hard drives for decommissioning and then, lo and behold, twelve of them disappear and the drives appear on eBay four days later”, she complains. These organizations fail to understand that they can delegate the task of processing data, but not the responsibility, Monaghan adds. “They’re not thinking it through.”

Even in the UK, where there are fewer discrete stakeholders in the healthcare value chain, privacy breaches can often happen inside an organization. That’s often down to people simply not following the process, or inherent process flaws.

“We get breaches about emails or faxes that have been sent inappropriately, or mail sent to the wrong address”, Monaghan explains.

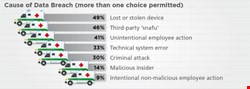

The Ponemon figures bear this out. Forty-nine percent of those surveyed reported lost or stolen computing devices, while 41% reported unintentional employee action as the cause of a breach.

A Technological Answer

Technology is one way to police such problems, says Ann Cavoukian, Information and Privacy Commissioner for the Canadian province of Ontario.

“The technological controls are worth their weight in gold”, she says, advocating role-based access controls so that healthcare organizations can tell when a breach has occurred. “There is a motivation for doing this, and once the initial expenditure has been made, the cost of maintaining the program is not severe.”

Such technocratic measures may miss the point. In many organizations, process breaches happen when stressed workers deliberately circumvent prohibitive security measures. Whistleblowers often tell the UK ICO that clinicians will use a smart card to log into a desktop system and then leave it logged in all day, even after ending their shift. “That’s down to culture”, Monaghan warns. “The doctor says that it takes too long to log into the system, and so it’s a workaround.”

Regulating Our Way Out of It

There are other ways to stop the rot, argues Dartmouth’s Anthony. Regulation is one method to help instigate and enforce systems and practices that limit the flow of information.

Susan McAndrew, deputy director for health information privacy at the US Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights, claims a set of clearly defined rules for health information privacy. “We expect health plans and healthcare providers to have in place a carefully designed, delivered, and monitored Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliance program that includes employee training, vigilant implementation of policies and procedures, regular internal audits, and a prompt action plan to respond to incidents”, she explains.

However, Anthony warns that regulation is inadequate. HIPAA contained the original privacy and security rules. They failed to account for this information exchange in the healthcare system, she says, adding that HIPAA was effectively table stakes legislation that would ideally have been enhanced at a state level.

“States that had more comprehensive regulations supercede HIPAA”, she says. However, as is often the case with security and privacy legislation, this regulation is patchy. Other US states had no legislation governing healthcare privacy and security, meaning that HIPAA became their de facto standard.

All this makes for a confusing patchwork of regulation. US healthcare entities are often local, but some parts of the healthcare system are more federal in nature, particularly when they affect population health, or involve interaction with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act required HIPAA-covered entities and their business associates to provide notification to HHS following a breach of unsecured protected health information, beginning in September 2009. This helped, but not enough, Anthony warns.

“The HITECH Act in 2009 strengthened, to some extent, the privacy and security rules in HIPAA, but there is still a lot of ambiguity about what is covered and how”, she says. “At the same time, we are rapidly rolling out [electronic] medical records.” Legislation is therefore constantly trying to catch up with technology as it affects current practice.

Health Records

Electronic health records are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it’s theoretically easier to copy a collection of records to a removable device and lose it than it is to copy a thousand paper-based files in a locked cabinet. On the other hand, as Cavoukian points out, it’s easier to maintain access logs and restrict access to specific parties.

There are several sector-specific solutions targeting the healthcare industry. Cavoukian cites one US-based firm called FairWarning, which provides log and audit access to health records. “This type of enterprise-wide privacy audit and breach detection tool is valuable because it analyzes who accesses the data and logs on a regular basis, and whether it is authorized”, she explains.

| "The fractured and fragmented healthcare system means that there are many different entities that touch your data" |

| Denise Anthony, Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice |

Regulating privacy and security into the healthcare community properly is a difficult but essential task. However, it is only one part of a multi-layered approach that includes technology and cultural adjustment. Behavioral change is a key part of encouraging a secure culture, Cavoukian says.

Technology, such as the FairWarning tools, can be used with training and awareness programs that explain why it’s important to restrict access to records.

“One hospital was having a problem with doctors and nurses talking out loud about the patients”, she says. The hospital put posters inside the elevators, showing one practitioner holding up a finger to their lips, saying “shhh!” Such visual reminders worked during the Second World War – so why not now?

Prognosis Mostly Negative

What is the prognosis for privacy and security in the healthcare sector? The patient needs serious care, warns Anthony.

This may get worse as healthcare reform takes hold. The US Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the Affordable Care Act means that tens of millions of Americans who were previously uninsured will now become part of the system. How will all of those extra patients be managed effectively?

Some positive measures are underway. Healthcare information exchanges (HIEs) are hubs that promise to help centralize and normalize the exchange of healthcare information between different stakeholders. However, the regulation for these exchanges is still in its infancy, and in spite of $564m in federal investment, a recent report from the US National eHealth Collaborative (NeHC) suggests that progress is slow.

As we crash headlong into the 21st century, we’re doing our best to remember Hippocrates. But we’re going to have to work a lot harder to get our healthcare security out of intensive care.