On May 23, 2012, Joshua Mauk got a nasty shock. Mauk, who works as an information security officer at the University of Nebraska, found that a critical database had been compromised on the school’s systems. It wasn’t just any database, either: it was the Nebraska Student Information System (NeSIS), which held the personal details of 654,000 students. The attack was targeted, and the intruder got administrative control.

“They got access to student data, financial aid and billing”, recalls Mauk, explaining that protecting networks in higher-education campus environments is often more difficult than in conventional private sector ones. “The main challenge with campuses is just that culture of openness”, he says.

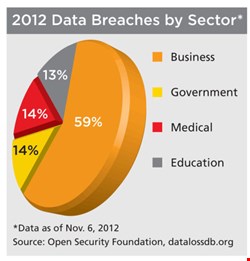

According to the Open Security Foundation, 15% of data breaches since records began have happened at educational institutions. These places – especially higher education establishments – face a unique set of challenges that keep people like Mauk on their toes.

Complex and Segmented

Many of these challenges are intimately bound together. For example, the network environment in universities is often sophisticated and intricate. This, in turn, is a result of higher education’s idiosyncratic organizational structure.

“We have lots of separate independent networks that are firewalled off from the main campus”, explains Jack Seuss, CIO at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

These fragmented networks are common because of the decentralized nature of most schools. Mauk explains that universities have at least three parts: academic, research, and business.

“We have to apply security strategies that segment these three components”, he says. “That’s been the challenge: moving from an open and flat network to a more segmented one.”

This inherent looseness creates challenges not only in technical infrastructure, but also in leadership and decision-making, explains Rodney Petersen, managing director for the Washington office of EduCAUSE, a non-profit association of IT professionals working in higher education.

“We are not a traditional enterprise. Our culture is decentralized in terms of leadership, decision-making, and IT infrastructure”, he relays. Private sector organizations operate at varying levels of cohesion; the employees in them, for the most part, work toward a common goal. Conversely, a university isn’t so much an institution as a set of loosely coupled functions. It employs some people, but is paid by others for the privilege of conducting research. It is a squirming bag of political and economic relationships.

When Users and Networks Collide

As if internal organizational and network structures weren’t enough, universities also have to worry about those pesky users, who are a diverse bunch. Aaron Massey, a postdoctoral fellow at the Georgia Institute of Technology, describes a syndrome, well understood among IT admins in higher education, called Eternal September.

Professors and IT staff used to get a constant stream of questions from clueless students in September, at the start of the academic year, as they grappled with networks and computing systems.

“A lot of people there are doing things for the first time. In a business, they are pre-evaluated for having a skill that is needed. That’s not the case in universities”, Massey explains. “Eventually, the questions stopped happening just in September, and became an eternal thing.”

Usability must be very easy for this user group, but as most security professionals know, usability and security are often diametrically opposed. “The more that you can simplify the scope of your security needs, the better off you are”, Massey adds.

The diversity of the user base makes it difficult for people like Seuss to use firewalls effectively. Young freshmen may have trouble logging onto a system, but at the other end of the spectrum, specialists will have specific technical needs. “Groups like computer scientists and mathematicians are trying to do all kinds of new research”, he says. “A lot of the time, they can’t be behind firewalls because it would stop them from doing what they’re trying to do.” Maybe they are monitoring a telescope and downloading images, and firewalls might interrupt this process, he explains.

Bring Your Own Problem (BYOP)

To compound the problem, both students and tutors like to bring in their own devices, and the explosion of post-PC hardware over the last two years has exponentially expanded the number of platforms. End points are notoriously leaky, and can not only bleed information out of a network, but can leak malware back in.

Some administrators solve this problem by completely blocking access to administrative systems from unapproved devices. Ian Short, applications infrastructure manager for IT services at the University of Winchester, locked down over 1500 Windows XP desktops on campus using PowerBroker Desktop, a system that centralizes their security and removes admin rights among users.

| "It's not really the device that you need to be concerned with, but the individual" |

| Aaron Massey, Georgia Tech |

The technology takes care of approved machines owned by the university that are connected to the administrative network. As for unapproved devices, “they can only connect to our wireless network”, he explains. From there, they can only gain access to the internet, effectively placing them in a demilitarized zone. Unapproved devices can then use administrative systems through a browser interface via HTTP. “They have browser-based access to their home shares, and for their email we use Microsoft Live@Edu into Office 365, so that all of their email is hosted off-site”, Short adds.

Tony Whelton, director of IT services at Wellington College in the UK, not only tolerates every student bringing their own device, but mandates it. “The majority of pupils seem to have at least two or three devices”, he says. As he looks across the prep school’s 400 acres of distribution points, he sees 3500 personal devices on the institution’s WiFi network.

Whelton is a good example of an administrator who bridges the gap between security and usability. “If people connect a device that is infected onto my network, the first thing that it will do is put a virtual firewall around that”, he says, using the ForeScout CounterACT Network Access Control (NAC) appliance to give the device restricted access and effectively quarantine it. “We don’t stop them from working”, he asserts. Whelton contrasts this with private sector environments he has worked in, where the user would simply be kicked off the network.

However, this won’t protect educational institutions against insider threats from individuals with access to the network. The University of Nebraska hack was the result of an insider attack, says Mauk. “Because they are inside our firewalls, they are inside our network. The risk is much greater.”

There Is an ‘I’ in ‘Team’

These challenges create the need for different approaches to IT security in higher education. Instead of being system-centric, security must be individual- and information-centric.

“Insider threats are a huge problem for these organizations”, says Georgia Tech’s Massey, who is a director of The Privacy Place, an academic research center. “It’s not really the device that you need to be concerned with, but the individual.”

“We must focus on the ‘I’ part of IT security, but the ‘T’ part is what’s taking over”, warns Petersen at EduCAUSE. “What we have been slow to recognize is that the information we have on campus – whether it’s the intellectual property of the academy, or more importantly the personally identifiable information – requires a similar level of high protection.”

| "We have lots of separate independent networks that are firewalled off from the main campus" |

| Jack Seuss, University of Maryland, Baltimore |

But while information lifecycle management is difficult enough in private sector environments, it is even more daunting to keep track of in traditionally open, decentralized university scenarios. Petersen argues in favor of sweeping organizational changes that elevate information to a first-class citizen within higher education environments.

Properly acknowledging information and the need to protect it would mean a centralized approach to issues ranging from compliance and risk management, through to auditing and even campus safety and security, argues Petersen. A central accountability department begins to sound like a good idea.

“I could imagine a division in the institution led by a chief accountability officer, where all of these things, including access for people with disabilities and copyright management, come together”, he says.

Risk Analysis

Perhaps from there, it might be easier to perform a cohesive risk analysis focusing on information on campus. Because of the wide-ranging nature of skills, roles, and goals among individuals and groups on campus, such an analysis would classify users, says Massey. “They all have different needs from the network”, he observes.

That risk analysis process would be campus-wide, says Petersen. Identifying and prioritizing the assets to protect is important in an organization as diverse as a university. “Then, coming up with mitigation strategies that address protections across categories of people, process, and technology, and then measuring, reassessing and repeating the process on an ongoing basis.”

Sharing is Caring

One important element here is information sharing. Cohesion on campus isn’t enough, experts argue. Sharing information between academic institutions to establish and reinforce best practices is a key part of the process.

EduCAUSE is one such collaborative hub. It hosts the Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC), which promotes security and privacy programs across the sector. Seuss points to another: Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs). Born from the US Federal cybersecurity strategy, these are sector-specific councils designed to share cybersecurity information, including threat calls, briefings, and white papers.

The education sector’s contribution to the ISAC movement is the Research and Education Network (REN) ISAC. It sends out over 100,000 notifications each year to 363 member institutions, including malware reports and vulnerability updates.

Openness may be one of the educational sector’s biggest weaknesses from a cybersecurity standpoint, but it is also one of its saving characteristics. “That’s one of the unique attributes of higher education: in general, but especially around the topic of information security, higher education establishments share information”, says Petersen. “Information sharing has been a trademark.”

A Swift Response

The University of Nebraska is just one of many educational institutions across the globe that continues to tighten their security. Mauk already had a security incident and event management system in place when the attack happened, along with a playbook for dealing with security breaches. The CIO closed off the network from third-party access, while the security team evaluated the situation and found an inside party responsible.

“We identified the individual within 12 hours, and police were notified and actually had spoken to the individual and confiscated their machines in 48 hours”, Mauk recalls.

Although the university notified all affected users of the compromise, over the next three to six weeks it narrowed the group of users at a higher risk from 600,000 to 150. In education, as elsewhere, compromises can happen. It’s how you respond that sets you apart from the pack.