Information sharing can be a win-win for public and private sectors, Phil Muncaster discovers, but there are still hurdles to overcome

Last year, pro-unionists looking to keep the United Kingdom from disassembling secured victory in the referendum on Scottish independence with a simple message: better together. It’s a message that governments on both sides of the Atlantic are looking to spread to private sector organizations struggling to contain the sheer volume and sophistication of modern cyber-threats.

Combining forces by sharing key threat intelligence between public and private sectors should be a no-brainer: a clear win-win. But it has been complicated in our post-Snowden world by fears of over-sharing information with intelligence agencies that indiscriminately devour private data. Then there are the ever-present concerns over possible legal action or shareholder ire if threat information indicating a data breach leaks into the public domain. It’s certainly not an easy sell for governments, and the patchwork of disparate frameworks, directives and legislation is growing ever more complex before our eyes.

At its very best, effective information sharing between public and private sectors should be a two-way street. On the one hand, government agencies and related parties would receive intelligence from a wide variety of endpoints on the ground to help them in ongoing investigations against state-sponsored hackers, hacktivists and financially motivated cyber-criminals. On the other hand, data flowing the other way – from the likes of GCHQ, the NSA and Europol – could be critical for CISOs and IT leaders hoping to pre-empt major attacks on their organizations and better fortify themselves against data loss.

Preventing such attacks and the data breaches which inevitably follow could save organizations millions. The most recent Ponemon Cost of Data Breach report put the average figure globally at $3.5m, 15% up from the previous year. The UK government, meanwhile, claimed in its Information Security Breaches Survey 2014 that the average cost for small businesses had risen from £35-65k to £65-115k, and for large firms from £450k-850k to £600k-1.15m.

What’s in Place

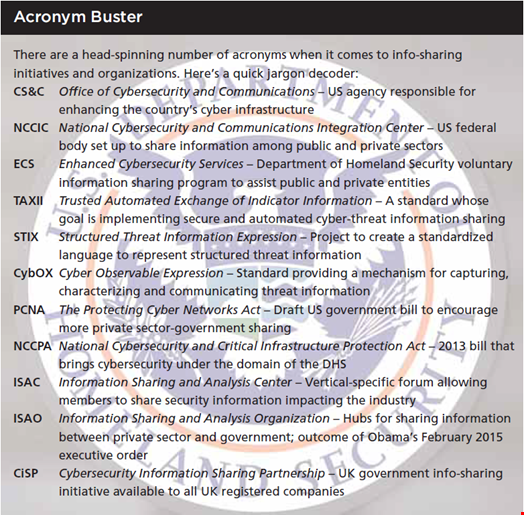

In the United States, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) Office of Cybersecurity and Communications, the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center, and US-CERT are heading up an over-arching strategy to “automate and structure” info-sharing techniques worldwide, both across industries and between public and private sectors. They’re doing this by promoting the use of three community-driven technical specifications – TAXII, STIX and CybOX – which, according to US-CERT, are designed to “enable automated information sharing for cybersecurity situational awareness, real-time network defense and sophisticated threat analysis.”

The DHS’s Enhanced Cybersecurity Services, meanwhile, is a voluntary info-sharing program focused specifically on critical infrastructure operators. The DHS also works with sector-specific Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) in industries including aviation, emergency services, health, nuclear, real estate, financial services and oil and gas.

In the UK, the coalition government created the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Partnership (CiSP) back in 2013. Now part of CERT-UK, it has 950 organizations and 2500 individuals signed up to receive real-time threat updates from the Fusion Cell, a joint industry and government team which creates alerts, advisories, regular summaries and bespoke threat analysis. There are also pilots under way to continue its work at a local level via Regional Organised Crime Units (ROCUs) established within the police force.

At a European level, there’s no single framework on info-sharing – legal or otherwise – spanning all sectors, although there’s a breach notification obligation on the part of telecoms firms to report to their regulators and at an EU level to ENISA. Data protection authorities also need to be notified if private data is impacted. Aside from the CiSP in the UK, there are other voluntary frameworks in member states such as MISP in Luxembourg, and NDN in the Netherlands.

A Problem Shared

But merely having such programs, whether they have legal backing or are voluntary, doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll be effective. The type of information shared can have a major impact on how useful it could be to the other party. Breach-related data such as timing, tools, techniques, procedures, and targeted sector can be incredibly useful, according to head of CERT-EU, Freddy Dezeure.

“More and more frequently the cooperation also involves the sharing of context in order to make prioritization of the information easier and to make the information actionable,” he tells Infosecurity. “A lot of work is currently under way to make sure that organizations speak the same language when sharing information with each other.”

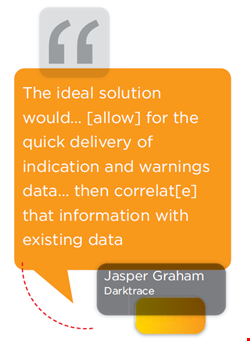

For Jasper Graham, senior vice president of cyber technologies and analytics at Darktrace and former NSA technical director, information needs to go beyond mere file hashes and IPs.

“The tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) have to be presented in a format that can be digested by everyone,” he tells Infosecurity. “The way hackers are going about attacking particular systems, or a notable increase in attacks across a certain industry vector could show a shift in the black market and a need for a particular data type. It is important to understand these shifts especially when working to stay a step ahead of the attackers.”

Bumps in the Road

Despite the proactive work being done by governments and other industry groups in this area, there remain serious concerns to address on both sides of the Atlantic before wholesale information sharing between public and private sectors can be achieved. These include doubts over how much information should be shared with agencies like the NSA and GCHQ, given the Snowden revelations of mass surveillance.

Then there are more practical concerns, such as privacy and anti-trust laws and the lack of a “single, well-accepted, machine-readable standard” for information exchange, according to Gartner research director, Joerg Fritsch.

“To give some examples, the public sector has to classify all information that would be good enough to support or threaten national security as ‘SECRET’; it cannot freely share this data. That includes data about threats to privately held critical national infrastructure where no security cleared staff and infrastructure that is accredited to store classified data are present,” he explains.

There are a number of emerging standards and architectures but no working and scalable blueprint, he adds, claiming that the current best channel is secured email – which is hardly scalable.

Fritsch also argues that another challenge facing current systems is that many emerging standards and frameworks seem to be driven by defense contractors, a fact which is keeping private sector participation low.

“If this is so, then it will stay a niche market tailored to the information sharing of players at selected CNI and governmental CERTS; it will hardly be a two-way system,” he adds. “I expect that the benefit for the CNI operator may be moderate.”

What Next?

A much-anticipated EU Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive – which would mandate greater information sharing, among other security measures – has yet to be finalized, but Fritsch is guarded about its chances of success.

“The public sector must for one get its act together to find out how it will ensure that the threat exchange will be a lively two-way street,” he argues. “Secondly it still must become more effective and understanding how an appealing public-private threat exchange partnership will be possible. The NIS direction is a good first step, but it does not solve anything yet. It is still very early days.”

In the US things are also heating up at a legislative level. An executive order signed by president Obama in February is designed to lay the framework for improved information sharing with federal agencies. In particular it will create new Information Sharing and Analysis Organizations (ISAOs) – which, unlike existing ISACs, will be more horizontal – and calls for common standards to share data more easily.

Elsewhere, much controversy still surrounds two pieces of legislation passing through Congress, which critics have branded surveillance bills in disguise: the PCNA and NCCPA. The PCNA in particular has been slammed by rights groups because it could allow law enforcement to use the data it collects to investigate crimes outside of cybersecurity. The bill also allows companies to hack back against assailants as a defensive measure, which could undermine current laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

For Darktrace’s Graham, a 14-year veteran of the NSA, governments and private sector need to agree on what data to share, how it can be used, and how it can be shared in a timely manner.

“From a very high level, the ideal solution would be a system that allows for the quick and easy delivery of indication and warnings data that then correlates that information with existing data from other companies to identify commonalities such as overlapping attack infrastructure, vectors, and exploitation methods,” he explains.

“This information would allow for the quick rollout and implementation of defenses within industry and government. Additionally, it will help to form a better picture of who is conducting the attack.”

There will inevitably be more challenges along the way. But if governments can agree on legally binding rules for information sharing, in consultation with all stakeholders, then perhaps before too long public and private sectors can really start to see the benefits of more openness.

This feature was originally published in the Q3 2015 issue of Infosecurity – available free in print and digital formats to registered users