The NSA has experienced its biggest legislative setback in nearly 40 years – but there’s a fishy smell to it, reports Danny Bradbury

*This feature was originally published in the Q3 2015 issue of Infosecurity – available free in print and digital formats to registered users*

Two years after Edward Snowden blew the whistle on the NSA, Congress has passed a law to rein in its powers. But will it really matter?

The USA Freedom Act finally passed on 2 June. It curtailed bulk data collection at the NSA, which had been vacuuming up metadata about domestic US phone calls and storing them in vast databases. This is the biggest legal ruling on surveillance since the mid-1970s, when the Church Committee was formed to investigate intelligence activities within the US government, following Watergate. It found a widespread telegram interception program, Operation Shamrock, dating back to 1945, whereby the NSA enlisted three US communications carriers to secretly provide it with copies of all telegrams sent to foreign parties. This also enabled it to gather information about US citizens on a secret watchlist.

The outcome was the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), which established an oversight procedure, and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) whose jurisdiction is activities relating to foreign intelligence.

A Long History of Surveillance

The Church Committee, recalled investigator L Britt Snider in 1999, “caused the NSA to institute a system which keeps it within the bounds of US law and focused on its essential mission.” Then came 9/11: one of whose outcomes was a culture of secret surveillance of US citizens, and, ultimately, the biggest exposé in history.

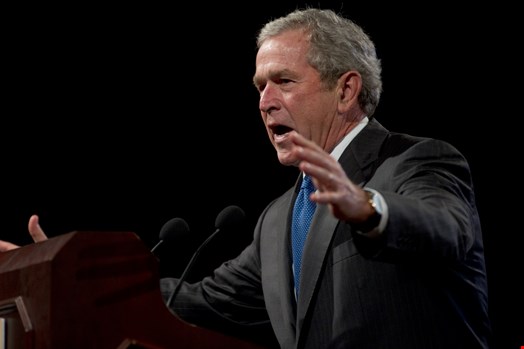

In 2001, President Bush signed an order allowing the NSA to monitor international telephone calls and email messages without warrants to search for terrorists. The agency, criticized by the 9/11 Commission for its adherence to strict oversight, began collecting information without applying for FISC approval.

It later transpired that the NSA had conspired with AT&T, BellSouth and Verizon to gather a vast database of domestic telephone call records. In 2013, the Guardian uncovered a court order requiring communications giant Verizon to give the NSA metadata from calls within its systems, both domestically and to other countries. That order was obtained by the FBI from the FISC, part of an ongoing bulk telephone metadata collection program authorized by the court in 2006.

The US government was then able to use these records to search all telephone numbers that directly communicated with a target, and also search any numbers that were in contact with those numbers (a second ‘hop’). Then, by conducting another third ‘hop’, NSA officials could determine who constituted a target. Making things worse, Section 215 of the Patriot Act, passed in 2001, made it easier for intelligence agencies to gather this and other information. It amended FISA, making it easier to gather information from both US and non-US citizens, and expanded the scope of surveillance orders.

Court Decision

Jim Sensenbrenner, who penned the Patriot Act, said in 2013 that bulk collection of call record metadata was “never the intent” of the legislation. Yet only weeks later, the American Civil Liberties Union sued director of national intelligence, James Clapper, and others in the government. The Union argued the program must be stopped and records purged, as such activities violate the first and fourth amendments. Its case was finally successful in May 2015.

"You're not allowed to collect surveillance data on people without probable cause. That separates us from East Germany"

By that point, Section 215 was nearing its end-of-life, due to ‘sunset’ on 1 June; Congress was busily working on extension legislation. The USA Freedom Act had already been voted down once in the 113th Congress.

A watered-down version of the bill, sponsored by Sensenbrenner, was under negotiation. It would extend the Section 215 provisions, but with significant caveats designed to quash the bulk collection of telephone metadata.

A Red Herring

The Act failed to pass by midnight on 31 May, leaving the intelligence community with dramatically reduced surveillance powers. Congress panicked. On 2 June, the bill was passed. The new legislation curtailed several collection methods. It targeted the collection of business records under Section 215, but also National Security Letters, which the FBI can use to demand customer records from organizations including telcos, while preventing them from informing customers.

The law also placed restrictions on the use of ‘pen registers’, devices that monitor specific phone lines. These were used to gather bulk metadata information until 2011, following a FISC-approved order in 2004. The USA Freedom Act requires that these collection methods be used with specific selectors to limit the number of records gathered. It also appoints an amicus as an independent voice in FISC hearings, which have hitherto been held in secret.

On the face of it, this sounds like great privacy reform, and a vindication of Edward Snowden’s whistleblowing. But privacy advocate and Resilient Systems CTO Bruce Schneier is highly critical: “It’s definitely vindication, but it’s also a red herring. It’s both at the same time.”

Retired NSA agent Kirk Wiebe, who worked at the agency from 1975 to 2001, has concerns about the act itself, and the adjustments voluntarily made by Obama in February 2014. He criticizes Obama’s ‘two hops’ limit: “Although collection is limited to two hops, what if the first hop from a suspected/known criminal or terrorist is the IRS? That would mean everyone who ever called the IRS is two hops from the bad guy and subject to collection,” he said. “So while pure bulk collection may end under the Freedom Act, ‘bulky’ collection is still possible.”

Plenty More Fish in the Sea

The act may have helped to quash bulk phone metadata collection using the mechanisms listed, but there are others. One of these is Executive Order 12333, a Reagan-era presidential order which carries similar powers to a federal law. Written 20 years before the web existed, this law permits the gathering of metadata and message content. Former NSA agent turned whistleblower, William Binney, is particularly concerned about section 2.3C of the order, which authorizes intelligence agencies to collect “information obtained in the course of a lawful foreign intelligence, counter-intelligence, international narcotics or international terrorism investigation.”

All of this creates a huge opportunity for incidental data collection about the communications of US citizens, he warns: “If you get any US data you can keep it and distribute it, as long as you’re looking for a terrorist or a dope dealer.”

“The NSA does that under that criteria, but they keep all the data they collect,” he adds. “Then the FBI and the CIA come in and look at the data internally in the US databases for anything that they want. There’s no oversight to that.”

EO 12333 isn’t the only way to obtain information on US citizens, warns Julian Sanchez, a senior fellow and privacy rights watcher at the Cato Institute. Section 702 of the 1978 FISA legislation also grants data collection powers, he points out. It is less egregious than Reagan’s order, still requiring a FISC review of data collection, although FISC plays no role in actually approving the target.

“At last count there are 90,000 targets under the authority. To my mind that fits as cleanly as anything could the definition of a general warrant,” says Sanchez. “All of those communications are intercepted, including the communications of Americans.”

Trawling for Data

Sanchez suggests that searching incidentally-collected domestic information stored in 702-related databases is a way of gathering information without a warrant, in what has become known as a backdoor search. This is what was taken out of the USA Freedom Act’s final version. “The proposal was that, if you wanted to search these databases for American communications, you’d have to take the same steps as if you did it directly. That was unfortunately removed.”

James Lewis, director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, has a different perspective: “The Freedom Act is useful because the NSA used to authorize itself, and that isn't how it's supposed to work.”

But ultimately, nothing much will change, he suggests: “It will change some of the procedures around collection and make the NSA and FBI jump through some additional hoops, but for communications surveillance, I don’t think it changes very much.”

The USA Freedom Act also curtails some mechanisms already ruled illegal by appellate court, including the direct collection of bulk call metadata directly by the NSA. However, it still leaves the data in the hands of the phone companies, and allows it to be queried by the NSA using targeted selectors.

This worries Gene Tsudik, a professor in the computer science department at the University of California, Irvine. “This stuff represents a treasure trove of information, and an attractive target for attacks,” he says. “I believe that if metadata has to be kept for some time, it is best to split it in a way that neither NSA nor the phone company can make sense of it, without cooperation.”

There are cryptography technologies for that, but there are no provisions for this as it stands. In any case, the NSA is still legally capable of collecting bulk metadata and (in some cases) bulk content on foreign targets which generate significant amounts of data on US citizens inside the country.

Should bulk data collection be a part of the US surveillance machine? “Against innocent people? No,” says Schneier. “That’s not what democracy does. You’re not allowed to collect surveillance data on people without probable cause. That’s not one of the things we do. That separates us from East Germany.”

The battle between privacy advocates and surveillance hawks in the US has been long. And difficult. And it isn’t over yet.

Timeline of Key Events

1945

- Government approaches telcos to secretly provide telegrams for national security purposes

1952

- NSA formed

1975

- Church Committee formed to investigate intelligence activities in the US

1978

- Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) passed to provide more oversight on foreign intelligence activities

1981

- President Reagan signs Executive Order 12333, which provides extensive information collection privileges to the US intelligence community

2001

- 9/11 attacks on US

- Patriot Act becomes law; Section 215 grants extensive information collection privileges to the US intelligence community

- President Bush authorizes the warrantless collection of data about international telephone calls and emails under Stellar Wind program

- NSA launches secret program to gather domestic US call data from telcos

2006

- FISA court authorizes bulk metadata collection program involving Verizon

2011

- Stellar Wind terminated (according to government officials)

2013

- Verizon metadata order publicly revealed

- ACLU sues intelligence community to discontinue bulk data collection

- Edward Snowden leaks thousands of documents to the press, detailing NSA programs

- ACLU case dismissed in district court

2014

- ACLU appeals decision

2015

- ACLU wins case in appellate court

- USA Freedom Act passes