Oleg Nikolaenko had just arrived in Las Vegas to check out the SEMA auto show being held last November, when all hell broke loose. FBI agents swarmed the Bellagio Hotel where he was staying and arrested the 23-year-old Russian citizen thought to be the mastermind behind the Mega-D botnet, capable of sending out 10 billion spam emails a day promoting counterfeit versions of Rolex watches, herbal supplements, and prescription drugs.

Nikolaenko was indicted in US federal court for violating the federal CAN-SPAM Act, which carries a possible prison term of five years. He is being held without bond in a Wisconsin detection facility by US Marshals.

Nikolaenko symbolizes the new face of cybercrime: a smart young Russian who uses his skills to make millions of dollars through cybercrime rather than through legitimate business in his home country.

Strong academic training in Russia combined with a lack of employment opportunities (exacerbated by the economic downturn in 2008–2009), have fueled the supply of young cybercriminals in Russia, observes Aleks Gostev, chief security expert with Kaspersky Lab’s global research and analysis team.

“The excellent technical schooling plays a role here together with a 10-year history of virus writing. With the advent of the financial crisis and economic instability, the situation deteriorated further – lots of IT graduates found it difficult to find jobs and turned to the ‘dark side’”, Gostev tells Infosecurity.

Sense of Impunity

Cybercriminals feel a “sense of impunity”, says Gostev. One problem, he believes, is the legal system. While the Russian criminal code contains prohibition of information security crimes, a victim has to file a written request with law enforcement before any action is taken.

“Unfortunately, Russian citizens are not always aware that they can approach the law enforcement agencies if their computer has been infected by malware. Moreover, some organizations, especially those in the banking sphere, may even try to conceal such incidents to protect their reputation”, Gostev notes.

“For instance, in 2009 a judge handed down a three-year suspended sentence in the case of a defendant who infected an ATM machine in St. Petersburg, stole PIN codes and bank card data, and withdrew millions of rubles from accounts. The judge commented afterwards: ‘So what? The computer was infected with a trojan. Is it really a crime?’”, Gostev relays.

Alexandr Vlasov, business development executive at Moscow-based Groteck Business Media, agrees that cybercriminals feel free to operate in Russia, a situation he attributes to gaps in legislation and insufficient training and awareness by law enforcement and security agencies that have responsibility for investigating cybercrimes.

However, Vlasov stresses that 90% of malware developed in Russia is targeted at Russian companies. This has prompted a response from domestic firms, which are starting to unite in their fight against malware and cybercrime, he adds.

This explosion of cybercrime has fueled demand for information security products in Russia. For most of the last decade, the information security market in Russia has grown at a rate of at least 25% per year, and in some years by as much as 40%, according to Vlasov.

Although the infosec market has been growing steadily, it hit a bump in the road following the worldwide financial crisis in 2008. According to analysts IDC, the Russian software security market declined 4.7% in 2009 to around $200 million. This compared to an overall decline in the Russian IT market of 40% to 60%, according to estimates cited by Kaspersky Lab.

| "Without the assistance of large Russian partners, it may be difficult for foreign companies to get to grips with the way business is done in Russia' |

| Sergey Zemkov, Kaspersky Lab |

Sergey Zemkov, managing director of the Caucasus and Central Asia for Kaspersky Lab Russia, said that the financial crisis was exploited by cybercriminals, which help to keep demand for information security products from plunging as much as the overall IT market.

“The end of 2008 and early 2009 was marked by the Kido (aka Conficker) epidemic, ATMs being infected with trojans, and theft via e-banking systems. That’s why many companies did their best to update their security protection systems”, Zemkov tells Infosecurity.

A law on protecting personal data, which was passed in 2006, was scheduled to take effect in 2010, but has been postponed until 2011, Zemkov notes. The anticipated implementation of the law has fueled a resurgence in demand for information security products and services, particularly in the auditing, consulting, training, and certification areas, he adds.

According to IDC research, Kaspersky Lab held the number one spot in the Russian security software market, with a 36.6% market share in 2009. The top five software security vendors also included ESET Russia, Informzaschita, Microsoft, and Symantec.

Market Changes

Groteck’s Vlasov identifies a number of critical changes in the Russian information security market over the past decade.

Firstly, large information security companies moved from selling single products (software, hardware, or software and hardware systems) mainly produced by themselves to supplying integrated systems produced by numerous suppliers.

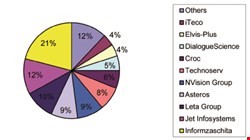

In terms of 2010 sales, the top 10 Russian security systems integrators, according to the Anti-Malware Test Lab, were: Informzaschita (21%), Jet Infosystems (12%), Leta Group (10.2%), Asteros (9.4%), NVision (9.3%), Technoserv (7.9%), Croc (6.0%), DialogueScience (4.7%), Elvis-Plus (3.7%), and ITeco (3.5%).

Secondly, the Russian legislature passed a number of laws requiring companies to adhere to international standards for information security, such as protection of personal data. In addition, new voluntary information security standards have been promulgated by industry, such as standards developed by the banking and telecommunications industries.

| "Unfortunately, Russian citizens are not always aware that if their computer has been infected by malware they can approach the law enforcement agencies" |

| Aleks Gostev, Kaspersky Lab |

Thirdly, large foreign vendors began entering the Russian market after receiving certification of their products and systems from the Federal Service for Technical and Export Control (FSTEK). These foreign vendors began signing partnerships with Russian companies, expanding their penetration of the Russian information security market.

The FSTEK agency, which is part of the Russian Ministry of Defense, was set up in 2004 by presidential decree. In addition to licensing information security technology, the agency oversees the country’s export control regime, including controlling the export of dual-use technologies that can be used for both civilian and military applications.

FSTEK certification is required for foreign vendors to supply information security products and services to Russian government agencies, which are estimated to make up more than half of the demand in Russia.

In addition, a network of private certification and test centers has developed that are recognized by the main market regulators, FSTEK and the Federal Security Service of Russia. The centers have been able to speed up the process of certification, enabling products and systems to get to market faster.

Foreign Firms

While the Russian government has tried to ease the certification process, it still poses a barrier to entry. Some of the large foreign companies, such as Cisco and Microsoft, have received certification for their products. But for smaller foreign firms, the process can be too expensive and time consuming to undertake.

The Russian government has been encouraging foreign investment in the information security sector, although it has not taken steps to make the legal and regulatory environment more attractive.

“The Russian government has, on a number of occasions, stressed just how important foreign investment is for economic development. However, judging by the response of foreign companies, those words have yet to be put into action. Without the assistance of large Russian partners, it may be difficult for foreign companies to get to grips with the way business is done in Russia”, comments Kaspersky’s Zemkov.

However, a major obstacle to foreign firms participating in partnerships with Russian firms is the lack of intellectual property protections, according to Zhanna Mingaleva, head of the National Economy and Economic Security Department at Perm State University, in Russia. The legislature did not enact comprehensive IP protections until 2008, and there are many rules that contradict the norms of international IP law, she tells Infosecurity.

Mingaleva identified a number of problem areas for IP protection in Russia: idea protection, invention protection, know-how protection, and agreements on technological and scientific cooperation.“The analysis of contracts often shows that foreign partners fulfill the terms of contract. When Russian partners are made to pay attention to the terms that ‘infringe their interest’, the common answer is that the foreign partner and the Russian partner meant completely different things” in the contract, Mingaleva observes.

In addition, corruption poses an obstacle to doing business in Russia. Mingaleva claims that “corruption in Russia is very strong and it makes it difficult to do business in Russia.” This is true for information security companies, as well as companies in other industries, she adds.

Despite the regulatory, legal, and corruption obstacles to companies doing business in Russia, the information security market is expected to continue its robust growth in the future.

Kaspersky Lab expects an 18% annual growth rate for security software products in Russia through 2015. Groteck Business Media predicts the overall information security market will grow at the rate of 10% to 15% in the near future.

Such healthy growth rates should offer more opportunities for young, smart Russian IT graduates, steering them away from the ‘dark’ cyber career path chosen by Nikolaenko and others.