Some would argue that our cities are already pretty smart. Glasgow has street lighting that brightens automatically as pedestrians or cyclists approach. Bristol is installing machine-to-machine sensors to supply superfast networks with data about energy use, air quality and traffic flow. Songdo in South Korea even has a waste disposal system that does away with garbage trucks and sucks your rubbish out of the kitchen via an underground tunnel network directly to the waste processing center. So what actually defines a smart city?

According to the British Standards Institution (BSI) the answer is “an effective integration of physical, digital and human systems in the built environment to deliver a sustainable, prosperous and inclusive future for its citizens.”

Unfortunately, explains Dr Gordon Fletcher, co-director of the Centre for Digital Business at Salford Business School, there are an awful lot of alternative definitions out there: “A straightforward summary is that [smart cities] all fall onto a continuum, from a light version which interconnects residences individually with various city systems (typically councils), through to a completely integrated system of residents, visitors and the various private and public organizational systems.”

All the Smart Things

What is on the ground now looks less futuristic than we might imagine. But if we were to let that imagination fly, what might we expect in terms of the positives of a truly smart city?

Helen Viner, chief scientist and research director at the Transport Research Laboratory, sees a number of benefits, from reduced congestion to more efficient energy use and enhanced public safety: “As our cities and the travellers within them become smarter, it’s likely that individual vehicle ownership will become less attractive and multi-modal transport options including car or cycle sharing more appealing.

“I expect that we will soon see a situation where people may choose between alternative cycling routes depending upon the live feeds of air quality information pushed to their smartphones or watches. Similarly, we can expect to see vehicle-to-vehicle communication become a critical element for the effective management of traffic around cities.”

Jacqui Taylor, CEO of FlyingBinary and a member of the Smart Cities Interoperability Committee at the BSI, thinks that each smart city needs a set of objectives which reflect the needs of its own culture and population.

“There is a need to move to more sustainable models of living which will create opportunities and make this an ideal environment to solve existing problems within a smart city framework” she says. “The move to a smart city allows the way we live and the services we consume to be reimagined, essentially creating a connected ecosystem enabled by IoT technologies.”

Indeed, technologists such as Andrew Rogoyski, director at CGI and chair of the TechUK Cyber Security Group, see smart cities essentially as containers for billions of smart things. Rogoyski also sees this creating battles for market share, with technology providers trying to establish dominance as platform, service and device providers.

“Initially this will generate a lot of diversity of proprietary platforms, protocols, hardware and software solutions,” he tells Infosecurity, “eventually streamlining to widely adopted technologies, platforms and protocols.”

The concern is that smart devices in smart cities will become too small, too numerous and too cheap to have an update strategy. “This means that security vulnerabilities discovered and exploited remain so,” Rogoyski warns. “Imagine implementing Patch Tuesday on the capital’s traffic light systems.”

Building a Smart – and Secure – Future

And so to the smart city negatives, which mainly revolve around security; but is bad security inevitable? Not everyone thinks so. Taylor was part of the team that developed the strategic smart city standards for the UK in 2014 and is currently working as part of BSI to create ISO standards using the UK standards as a base. She sees this as an evolving landscape to be tackled via the collaboration between emerging standards within national boundaries.

“Smart cities are closed systems,” she explains, “they have in-built controls to monitor normal activities and the systems will flag signals in the general noise to determine patterns of change.”

So while each city will need to determine its own strategy for cyber-espionage, the cloud services which curate the data will have controls built in to detect and monitor any activity deemed to be a threat. “It is unlikely that the majority of the sensor technology will need to have additional security around the individual streams of data,” Taylor insists.

Fletcher also sees some positives, not least that, in a fully-realized smart city, anomalies within individual systems could be identified early and analyzed and understood precisely in relation to other systems in the smart city. “This could reduce false alarms and enable security analysts to trace a path to the perpetrators” he suggests.

That said, Fletcher also admits that there are already too many examples of poorly secured technology to reassure anyone that all of the components currently in the city are fully secure. What about infrastructure technology obscurity or isolation, would these be enough in terms of IT security from the smart city perspective? Fletcher doesn’t think so, seeing them as a trade-off to participation in the smart city.

“In this sense commercially it would be undesirable to take this route towards IT security. It would act as a barrier to the achievement of a genuinely functional smart city” he says. “Both approaches would inevitably necessitate workarounds that would be to the detriment of the smart city’s efficiency.”

Obfuscation is never a successful long-term strategy at any level for technology and in some ways this approach presents itself as a challenge to hackers. One thing is for sure: as soon as anything becomes connected, a whole new set of security challenges are introduced. Could intelligent traffic management systems be targeted by those seeking to cause accidents by altering the timing of the traffic signals?

Better Understanding, Better Outcomes

“Currently not enough is known about the security risks to smart cities and a connected infrastructure,” Viner admits, “so it’s vital that further research is undertaken to identify threats and ways to mitigate risk.”

Smart cities bring about a wealth of new opportunities in regards to data analysis and sharing. Rather than being viewed in silos, data in areas such as asset management, safety, air quality, traffic volume and congestion could be analyzed holistically, providing organizations such as road operators, insurers and local councils with a better understanding of movement throughout the city, and impact on the environment.

“At the same time, it could reduce the ability to be anonymous which in turn introduces additional privacy risks,” Viner warns. “In such circumstances, we need to have educated and informed debate about the risks and benefits of such approaches.”

Although it would seem, at first glance, that any big data and machine-to-machine driven city structure was bound to be bad for citizen privacy, an Orwellian dystopia may not be inevitable. “We cannot expect to move to a connected ecosystem with the same approach to privacy,” insists Taylor. “Since the Snowdon revelations there is a general issue from a citizen viewpoint that ‘surveillance’ will not be accepted.”

This is particularly important as we move towards a world where Generation Y has reset the privacy agenda. This generation has two golden rules: if you do something in my name you need to tell me, and don’t be creepy.

“Smart cities will need to build their use of data based on trust, particularly where there is use of citizen data,” Taylor warns. This allows for new trust and privacy models to be explored and the curation of the city data on behalf of citizens or the city, on either a monetization or direct benefit basis. It’s not just the cities that will get smarter; so will our approach to dealing with the security and privacy issues of evolving technology.

NetWars CyberCity

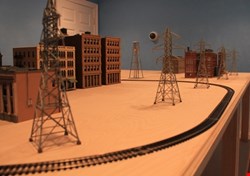

Infosecurity spoke to Ed Skoudis, Fellow at The SANS Institute, regarding a smart city it has built in 1:87 scale miniature. Working on the basis that smart cities are happening now, with most critical systems already controlled by networked computers in a way they were never originally intended to be, SANS built the CyberCity project as a research platform to help better understand the impacts of everything from SQL injection through to buffer overflows and beyond.

“It’s a physical city in miniature form (6 by 8 feet in size on top of a table),” Skoudis explains, “but under the table we’ve included real industrial control equipment that you’d see in life-sized power grids, water treatment facilities, and more.”

As well as the research element, this virtual smart city in miniature is also used as a ‘cyber range training environment’ for military personnel, law enforcement, and utility providers. It’s an essential tool in demonstrating to senior leaders and planners the potential impacts of cyber-attacks and cyber-warfare.

This feature was originally published in the Q3 2015 issue of Infosecurity – available free in print and digital formats to registered users