"The attack could have spread further, save for the discovery of a 'kill switch' within the WannaCry code."

Stephen Pritchard explores how a ‘weaponized’ exploit and home-brewed ransomware brought global systems to a standstill

Friday May 12 may yet be seen as a turning point for global IT security. WannaCry, a fairly basic piece of ransomware code, spread through a known exploit in Microsoft Windows, went on to infect more than 200,000 computers in 150 countries within two days, according to Europol.

The attack could have spread further, save for the discovery of a ‘kill switch’ within the WannaCry code. The ransomware was written to detect if it had been trapped by a sandbox, by calling up a fictional URL. If it detected a sandbox, the code would shut down.

A security researcher, known as MalwareTech, spotted the behavior and registered the kill switch domain, forcing the WannaCrypt software to shut itself down, but not before infecting organizations including the NHS, Telefonica and Deutsche Bahn (German railways).

Train services were disrupted, and in the UK, hospital appointments and operations were cancelled. Much of the damage, according to Ken Allan, a security expert at PA Consulting Group, came not from damage to IT systems but because organizations were forced to revert to paper processes. “A lot of resilience comes from not having 100% digital infrastructure,” he says, but as organizations seek greater efficiency through automation, “that will diminish.”

"This was an incredibly powerful zero-day loaded up with rubbish malware."

Mind the Gap

It could have been much worse: “This was an incredibly powerful zero-day loaded up with rubbish malware,” explains Ken Munro, partner at Pen Test Partners. “One reason it propagated so quickly was because it got inside the NHS N3 private network.”

The prompt action of security researchers, coupled with the basic – or even amateur – nature of the WannaCrypt software, contained the outbreak. “The kill switch has helped relieve a lot of pressure on organizations, including the NHS”, points out Darron Gibbard, chief technical security officer at Qualys.

According to Raj Samani, spokesperson for NoMoreRansom and chief scientist at McAfee, the attackers appear to have raised relatively little money through the ransomware. It is entirely possible – now that law enforcement are watching the Bitcoin wallets used to funnel ransoms – that the hackers will never collect the money. Few, if any, victims have received decryption keys, he suggests.

However, the rapid spread of WannaCry shows a weakness in many organizations’ security policies. The malware spread by exploiting a vulnerability in older versions of Microsoft operating systems, including XP.

Unlike the ransomware, the exploit itself was relatively sophisticated, and used Windows SMBv1 and SMBv2 to spread across networks. The vulnerability itself was patched by Microsoft in March this year. Although it is unusual for Microsoft to issue patches for unsupported operating systems, the company did so in this case, and marked the patch as critical.

The exploit itself is a subject of further controversy. WannaCry spread through a worm, part of a haul of malware code stolen from the NSA in April by a group called Shadow Brokers. “The NSA had a ‘weaponized’ strain”, says Kirsten Bay, CEO, Cyber adAPT.

Technology organizations and security experts have been critical of the NSA’s handling of the exploits, and the agency’s failure to disclose their discoveries.

Microsoft’s president and chief legal officer, Brad Smith, has not held back. “Repeatedly, exploits in the hands of governments have leaked into the public domain and caused widespread damage,” he wrote in a blog post published on the company’s website days after the outbreak. “Governments of the world should treat this attack as a wake-up call”, he added.

Whether intelligence agencies will change the way they collect, modify and store malware remains to be seen. After all, these organizations’ mission is not just to detect malware, but potentially to modify, exploit and use malicious code and vulnerabilities for intelligence gathering, or to retaliate against bad actors, including nation states.

National computer crime agencies, though, have moved quickly to provide advice and support for affected organizations. The UK’s newly formed National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), itself part of the intelligence agency GCHQ, has issued comprehensive advice for dealing with WannaCry and other ransomware attacks, but organizations need to do more than address the specific issues caused by the WannaCry outbreak.

Cry Wolf

The first and most fundamental step CISOs need to take – if they have not already done so – is to apply patch MS17-010. If organizations cannot apply the patch, or disable SMBv1 – perhaps because it is not possible to interrupt critical systems – then the NCSC’s advice is to isolate the legacy system from other hardware on the enterprise network.

“Security patching is just a normal and regular thing organizations need to do”, argues Yossi Shenhav, co-founder and consultant at Israel-based Komodo Consulting.

The second step is to review security procedures, including patching. There are plenty of practical reasons for organizations to continue to run systems such as Windows XP.

Criticism aimed at the UK’s NHS, and other bodies caught out by WannaCry, has suggested that CIOs have under-invested. This might be the case in some organizations, but for others, the need to run legacy, bespoke or customized software makes migration difficult. Even Microsoft’s own Office 2007, still used in many organizations, will not run on Windows 10.

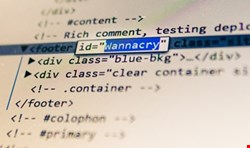

Failing to patch systems is harder to justify, although some companies have strict policies for testing patches before deployment. Patch management services and tools should provide CISOs with the breathing space they need to allow systems managers to test patches; if a patch cannot be applied, then isolating systems is the next best step.

Security teams could also make better use of the logs and monitoring data they already gather, to improve warning signs of any attacks. Early warnings and improved threat intelligence gives CISOs the chance to brief end-users of potential exploits and malware.

WannaCry may have used SMB to spread between systems, but ransomware is more often spread through phishing attacks. Effective user education is just as important as technology to contain the spread of ransomware, and to limit its impact on the business.

"Governments of the world should treat this attack as a wake-up call"

Test and Test Again

The most important lesson from WannaCry, though, applies to both organizations and individual users: to check and test data recovery plans. With few WannaCry victims receiving keys, the best advice is to use backups to restore clean versions of operating systems and to recover data.

However, if organizations, or individual computer owners, have not backed up their data, and have not tested their ability to restore backups, the impact of ransomware will be much more severe.

“The most important thing is for CISOs to simulate systems being held to ransom, and test-drive their disaster recovery,” says Munro. “Grab the playbook for how to deal with this type of incident, and run through it.”

Effective backups and recovery testing will help organizations restore operations quickly, avoiding the need to pay for decryption keys. This keeps money out of the hands of criminal networks. “It’s an important point to remember: this is not random code running around networks, but a criminal act”, adds Ms Bay. That realization may be the most effective way of all to cut down on future attacks

Case study: NHS: Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Western Sussex Hospitals, a UK NHS Foundation Trust, was able to avoid WannaCry through effective IT security management.

“Although we were unaffected by the outbreak, we still had a number of systems where the patch had not been applied because we could not get system downtime from our user base. This was subsequently quickly agreed,” explains Grant Harris, head of IT operations.

“We patch all Microsoft, Chrome and Adobe products within a week of release. We release Microsoft to a subset of our users. If we get no issues, we then release the patch to the rest of our desktop estate. Most servers are patched at 2am every Monday.

“We had already purchased and installed Sophos Intercept X and are in the process of buying Palo Alto next-generation firewalls to protect our sites. Legacy systems are an issue.”

Harris hopes that NHS England will be able to put pressure on suppliers to allow critical systems, especially those in clinical areas, to accept patches.

In the meantime, though, user vigilance is an important part of the strategy. “We didn’t have any unusual network activity; however subsequent analysis of our Puremessage email AV tool showed 30-times more blocked emails than usual,” says Harris.

“We continually remind users now about vigilance when opening emails, even though this doesn’t appear to have been the vector for infection – but patching is key. Most attacks utilize known vulnerabilities. Patching is the cheapest option available to protect your assets.”