What do FoxBalde, HermeticWiper and DriveSlayer have in common? They are all same wiper malware deployed against Ukrainian organizations on February 23, 2022, several hours before Russian troops set foot on Ukraine’s soil.

The only difference, they were named by three different vendors, Microsoft, SentinelOne and CrowdStrike respectively.

This is not an uncommon complication. WhisperGate and Paywipe for instance are names used to talk about a separate wiper attack launched a month earlier, the former has been coined by Microsoft, and the latter by Google’s Mandiant.

If you’re confused, so are we. Threat intelligence analysts themselves also admit the naming conventions can get out of hand.

Chris Morgan, a senior cyber threat intelligence analyst at ReliaQuest, admitted, “Naming has always been a bone of contention in the cyber threat intelligence (CTI) community.”

Based on the discussion on Twitter by fellow researchers and discussing this naming at #ESETresearch, we will continue to call this malware #HermeticWiper 7/n https://t.co/CsDZYKFMlg

— ESET Research (@ESETresearch) February 23, 2022

It becomes even more confusing when we examine the origin of cyber-attacks as threat groups themselves also receive different names and identifications.

For instance, CrowdStrike attributed the WhisperGate/Paywipe attack to Ember Bear in March 2022, and Mandiant attributed it to the ‘uncategorized’ activity cluster number 2589, or UNC2589, in July 2022. In its recent Fog of War report, Google Threat Analysis Group (TAG) named UNC2589, Frozenvista.

We are left in a tricky situation: while both CrowStrike and Google’s two threat intelligence teams agree that the threat actors behind the WhisperGate/Paywipe attack have strong links with Russian intelligence – most likely the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency – it is impossible to claim that Ember Bear is UNC2589/Frozenvista. In its ATT&CK framework used by most, if not all, vendors, non-profit MITRE referred to UNC2589 as one of Ember Bear’s “associated groups.”

It has become common practice in the cyber threat intelligence (CTI) community to use different names interchangeably when referring to more established nation-state-sponsored groups such as Sandowrm (aka Voodoo Bear, Iridium and Frozenbarents) or APT28 (aka Fancy Bear, Pawn Storm and Sednit), both linked to Russia.

The Sober and the Superheroes

While cyber attribution informally started several decades ago, the APT1 paper launched in 2013 is signalled by some as the first time anyone called out an espionage group.

In APT1 Mandiant identified China’s PLA Unit 61398 as the first advanced persistent threat (APT) group.

“It marked the birth of commercial cyber threat intelligence,” Jamie Collier, an EMEA senior threat intelligence advisor at Mandiant, claimed.

Since then, every cybersecurity vendor with a threat intelligence team has developed its own naming convention.

Some use codenames and numbers, including Mandiant (UNC2589, Temp.Warlock, FIN11, APT28…), MITRE (G1003, APT28…) and Microsoft (DEV-0537…).

“We use a sober, or even dull, naming convention because we don’t want to glamorize those groups. And a lot of what MITRE uses in terms of attribution comes from Mandiant,” Collier told Infosecurity.

Others are more creative, using combinations of fanciful names, sometimes referring to elements linked to the groups or their modus operandi:

- The country of origin: CrowdStrike’s Pandas, Kaspersky’s Dragons, SecureWorks’ BRONZES and Palo Alto Networks’ Tauruses refer to Chinese actors, for instance

- The type of attacks: Palo Alto Networks’ Orions are for business email comprise, for example

- The motivations: CrowdStrike’s Spiders, SecureWorks’ GOLDS, Palo Alto Networks’ Libras and Trend Micro’s Waters are given to financially motivated actors

- The vulnerabilities the threat groups use (Symantec)

Others use names completely made up, like Microsoft’s Strontium or Dragos’s Talonite.

“It all comes down to the creating influence of the threat analysts. But to be honest, these names also help us to remember things. Take Spectre and Meltdown [two major vulnerabilities found in microprocessors in 2018], for instance. I remember them because of their names, not the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) number. There are people in this community who would remember every CVE number, and I’m certainly not one of them. It’s the same with threat groups,” Morgan noted.

"Different threat intelligence teams might be looking at the same puzzle, but we're not necessarily looking at the same pieces, and our lens does not always have the same focus."

Florian Roth, head of research at Nextron Systems, is also very fond of those names. In 2018, he launched a spreadsheet tracking different threat group names and vendors’ naming schemes that is still available today.

In a blog post introducing this work on Medium, he wrote: “We secretly love these names. They shed a different light on our work — the tedious investigation tasks, the long working hours, the intense remediation weekends and numerous hours of management meetings. If the adversary is Wicked Panda, Sandworm or Hidden Cobra, we perceive ourselves as some kind of superheroes thwarting their vicious plans. These names create an emotional engagement.”

A Rosetta Stone of Cyber Attribution

The partisans of a “sober” naming system and the CTI analysts who enjoy being perceived as “superheroes” are unlikely to be reconciled.

However, CTI analysts admitted to Infosecurity that clients ask them why they should deal with so many naming flavors, why we cannot invent a ‘Rosetta Stone of cyber attribution,’ Shanyn Ronis, a senior manager in Mandiant's threat intelligence team, put it.

ReliaQuest’s Morgan said, “Of course, since private companies mainly lead CTI, each team wants to keep some competitive edge amongst the cyber community and not piggyback their findings off names other cybersecurity companies have used.”

However, the main reason many CTI analysts are skeptical about a standardized naming convention “comes down to analytical precision,” Collier claimed.

“Since each vendor’s tracking methodology is different, every team is working off different datasets, so we have a different visibility,” Ronis developed.

Feike Hacquebord, a senior threat researcher at Trend Micro, agreed: “We might be looking at the same puzzle, but we’re not necessarily looking at the same pieces, and our lens does not always have the same focus.”

The current system allows each CTI team to make sure that their naming reflects the underlying work they’ve been doing, Ronis explained. It also allows vendors to be flexible, merging or disbanding threat groups and sometimes disagreeing with one another.

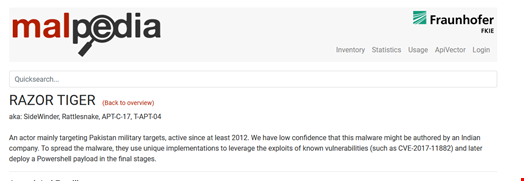

Illustrating this, Feixiang He, an adversary intelligence research lead at Group-IB, said, “For instance, a few weeks ago, based on the overlaps in command-and-control (C2) servers and tools, we concluded that SideWinder and Baby Elephant are most likely the same or closely related APTs.”

This explains why MITRE refers to the previously mentioned UNC2589/Frozenvista and Ember Bear as “associated groups.” They may eventually be merged in the future.

Ronis continued: “Cyber attribution is not always a one-to-one game. Even when the threat activity of different groups overlaps, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the same group. Collapsing different things into one category can make us make mistakes over time.”

This happened with the Winnti threat group. First coined in 2013 by Kaspersky to identify a threat group behind an attack based on a malware family previously named by Symantec (now Broadcom), the name was used, or Kaspersky’s work referred to, by several vendors over the years, for clusters of threat activity that were most likely slightly different, leading to considerable confusion in the CTI community as to who Winnti are.

Towards New Threat Categories?

According to Mandiant’s Collier, the current system of independent threat tracking is even more critical with the emergence of the ransomware groups and their affiliate model.

“Since there might be several groups behind an attack, each responsible for one piece of the cybercrime-as-a-service (CaaS) operation, we need even more rigor in whom we attribute cyber-attacks to,” he said.

Recently, the lines between financially and geopolitically motivated groups have been blurred since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. This could lead the CTI community further from a ‘Rosetta Stone of cyber attribution.’

“I believe the spectrum of cyber attribution is going to become more and more difficult to define, particularly in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war, because we have seen a lot of different groups emerging whose identities are questionable, who present themselves as hacktivists of ransomware groups, but are acting on behalf of a nation-state. This, again, makes it more critical to focus on what we can back with our previous work,” Ronis said.

Rather than simplifying naming conventions, some in the CTI community even call for new categories encompassing these hybrid groups. For instance, Derek Manky, global vice-president of threat intelligence at Fortinet, now refers to these groups as advanced persistent cyber-criminal (APC) groups.

However, having separate naming conventions should not mean working in siloes, Roth argued. “It is still crucial that they keep linking their research to the research of others, pointing out partial or full indicators of compromise (IOCs) overlaps and alignments with previously reported operations based on the respective TTPs. Otherwise, mapping the different threat actors’ names becomes an irresolvable task.”

Morgan nodded: “Working with partners and transparently cross-referencing each other in the threat intelligence community is key to useful cyber attribution. The MITRE ATT&CK framework has done a lot to standardize how we talk about tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). Now, it’s down to governments to encourage vendors to cooperate as much as possible.”

This article is the second part of a three-part cyber-attribution series that has been published on Infosecurity’s website.

Part 1 - Threat intelligence: Why Attributing Cyber-Attacks Matters

Part 3- Threat Intelligence: The Role of Nation-States in Attributing Cyber-Attacks