A glimmer of hope remains for the UN's proposed Cybercrime Treaty as negotiations look to resume this summer after being on hold in New York since February.

However, experts still question if the Russia-led resolution will become a helpful tool in the fight against cybercrime or an unfortunate ally to authoritarian regimes.

How the Cyber Peace Treaty Came About

Initially proposed by Russia to the UN in 2017, the Comprehensive International Convention on Countering the Use of Information and Communications Technologies for Criminal Purposes (commonly referred to as the Cybercrime Treaty) is designed to create a globally agreed legal framework to combat online fraud, scams and harassment.

In addition, it will be used to help define how countries investigate and criminalize cybercrime-related matters.

The Treaty is also a way for Moscow to push for an alternative to the 2004 Convention on Cybercrime (aka the Budapest Convention), a similar initiative drawn up by the Council of Europe.

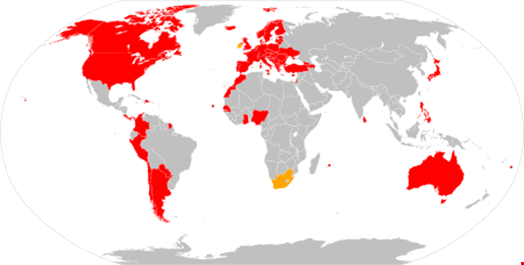

Today, 72 countries have signed the Budapest Convention and 70 have ratified it, however, major economic powers like Russia, China and India have not.

Formal negotiations for the new Cybercrime Treaty began in 2021.

On January 29, 2024, UN member-states and over 200 accredited stakeholder organizations gathered in New York for the concluding session of the Ad Hoc Committee (AHC), led by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Kaja Ciglic, senior director for digital diplomacy at Microsoft, took part in the negotiations. “This was the first time so many non-state organizations were invited to participate in the negotiations of a UN convention,” she told Infosecurity.

“We at Microsoft get vetoed all the time, mostly by Russia or sometimes China. At least, this time, we have a voice in the negotiations – and we’ve tried to use it.”

The session ended on February 9 without UN member states reaching an agreement.

The Latest Draft Facilitates Cybercrime, Rather than Address It

Contentious Articles

The latest draft is a 77-page document including 67 articles divided into nine chapters.

In this document, the following articles remain void, suggesting that an agreement has not been made between member-states:

- Article 5: Respect for human rights

- Article 17: Offences relating to other international treaties

- Article 24: Conditions and safeguards

- Article 35: General principles of international cooperation

According to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, two of the most contentious issues concern Articles 5 and 24, human rights and safeguards.

The Global Initiative wrote in a blog post: “From the outset of day one of the negotiations, some member states (including Iran) did not want any explicit reference to human rights in the treaty, arguing that the cybercrime treaty was not a human rights treaty and that a similar approach to the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) should be taken (i.e. no reference to human rights included).”

This position was opposed by a number of member states including Western countries and some countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa.

Questioning the Convention’s Scope

Notably, Articles 5 and 24 are supposed to allow exceptions for what is considered a cybercriminal act under the future convention, protecting individuals in two situations:

- Security researchers breaching IT systems for the general interest

- Citizens to freely express ideas only and enjoy their human and digital rights without reprisal

Microsoft’s Ciglic explained: “The text Russia proposed in the first place was very bad. There has been progress, both in the definition of what cybercrime means – which is a lot narrower than initially suggested – and security research protection provisions, but it’s still far away from what we’d want the text to be.”

In terms of human rights protection, Ciglic said, we’re even further away from an acceptable proposal.

“The latest draft still allows search and seizure requirements to be made in secrecy, which opens up to quite a lot of abuse. There are not enough safeguards, such as the right to appeal, or to call for an independent oversight in case a government uses the convention as a legal basis for indicting someone. From the start, Microsoft has advocated for a very narrow treaty,” she explained.

Cross-Border Data Sharing Concerns

Many stakeholders cited the Treaty’s potential to authorize states to carry out intrusive cross-border data collection, devoid of prior judicial authorization and genuine oversight and conducted in secrecy, as a critical concern.

According to Nick Ashton-Hart, the head of delegation to the negotiations for the Cybersecurity Tech Accord, the latest draft remains “deeply problematic.”

“It allows governments to exchange citizens’ personal information globally in perpetual secrecy if they choose to, and to leverage the powers of the Convention to cooperate on any crime that any two countries agree is a crime that uses technology in even the most basic way. This can be as trivial as the use of a modern smartphone to place telephone calls.

“The text does not allow providers to object to any request unless individual states choose individually to let them, which will undoubtedly create more conflicts of laws problems, where providers are told to break the law in one jurisdiction to follow it in another – a problem that already exists today in law enforcement cooperation, which delays or frustrates cooperation entirely when it happens.”

The current provisions would “facilitate cybercrime rather than address it,” he concluded.

Civil Society and Industry in Agreement

Generally, Ciglic said that the collaboration between civil society associations, NGOs and industry organizations to defend these safeguards throughout the negotiation process was unprecedented.

Pavlina Pavlova, a public policy advisor at the CyberPeace Institute, agreed.

“The AHC process has united civil society and industry opposition in a way I have never seen in international relations. Many stakeholders are aligned on those criticisms and collaborated on several joint initiatives, like open letters and amendment proposals,” she told Infosecurity.

Conditions for a Beneficial UN Instrument Against Cybercrime

Pavlova remains optimistic that the future negotiations can result in a helpful UN instrument while safeguarding against human rights violations. “Everything is still open,” she says.

She argued that since there are only a handful of regional conventions on cybercrime, including the Budapest Convention and the Malabo Convention, and no international one, the Cybercrime Treaty negotiations are a great opportunity to “streamline global efforts in the fight against cybercrime.”

"I don't think the outcome has been decided yet. That's why it's so important to engage now."Pavlina Pavlova, Public Policy Advisor, CyberPeace Institute

However, she conceded that for this to become reality, negotiators would need to adopt a text with:

- A narrower definition of what cybercrime means

- Incorporate human rights safeguards

- Amend the cross-border exchange surveillance provisions included in the latest draft

“The scope of the Treaty should be narrow and based on international standards. A broad scope of criminalization increases the likelihood of duplication and contradiction with existing frameworks and endangers the exercise of human rights online. There is a particular danger that if the treaty criminalizes content-related offenses, it will lead to violations of freedom of expression globally.” she explained.

For instance, she said there are no internationally agreed-upon definitions for extremism or terrorism-related offenses.

"If any of these terms become part of a legally binding treaty for cyberspace, it can be easily abused by authoritarian regimes to infringe on free speech."

While these references have been averted in the latest drafts, other provisions expand the scope to a wide range of offences related to other international treaties. "As it stands, the Treaty is not fit for purpose" she added.

Ciglic is less hopeful and said that with how the whole process has started, she is not sure the Treaty can ever be a beneficial instrument that causes no harm.

“Ultimately, it will be a compromise, not a text that Microsoft or civil society would want to see. We’ll see how bad it is,” she told Infosecurity.

However, she agreed with Pavolva’s conditions for the text.

Ashton-Hart said that there are still “a few bright spots” in the negotiations and noted that some of the delegations have made proposals to address some of the Cybercrime Treaty’s issues.

Canada’s and New Zealand’s efforts during the negotiations have notably been focused on clarifying some provisions, including the scope of cooperation on electronic evidence, to avoid misinterpretations and ensure the respect of human rights.

Next Steps for the Cybercrime Treaty

The next official negotiations are set to take place in New York in the summer of 2024. In the meantime, informal discussions will likely occur between member state delegations but without accredited stakeholders.

According to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, there are three possible scenarios at this stage:

- Scenario 1: Funding and UN General Assembly approval are secured for another meeting in July 2024 (or perhaps earlier). If so, delegates would, in the meantime, work to find a consensus so that they would be able to adopt a treaty

- Scenario 2: Funding or agreement is not secured within the UN to continue the process, or governments delay the approval of funds as a political tactic to stall the overall process, and the process gets shelved, meaning there would be no final treaty

- Scenario 3: A country or group of countries bypass the AHC process and bring a draft to a vote at the General Assembly. This would mean a simple majority would be needed to approve a treaty. It is unclear which way that vote would go

Why the Outcome of the Treaty Matters

There are many steps before the text becomes an official UN instrument:

- Member states need to set the threshold condition for adoption (Russia’s initial proposal, that five countries ratify the text, has lately been updated to 40, other countries call for a 60-ratifications threshold)

- Member states need to agree on a final draft

- The final draft needs to be confirmed by the UN General Assembly

Once all these steps have been confirmed, UN member states are free to sign, ratify and translate the agreement into their domestic laws.

Pavlova said that initially, many countries – especially signatories of the Budapest Convention – were skeptical of Russia’s proposal, considering there was arguably no need for another treaty on cybercrime.

Others saw the opportunity to share information and get more powerful nations' help in their fight against cybercrime.

Ciglic explained: "Many countries are desperate to have a tool that would help them address cybercrime. They look at a legal framework as such a tool.”

However, she added that this also means that, if the Treaty becomes a UN instrument some member states will copy and paste it without thinking of safeguards or risks it could pose.

“It will be interesting to see how many countries are willing to compromise based on the perception that having a text is better than no text,” she said.

Pavlova concluded: “I don’t think the outcome has been decided yet. That’s why it’s so important to engage now.”