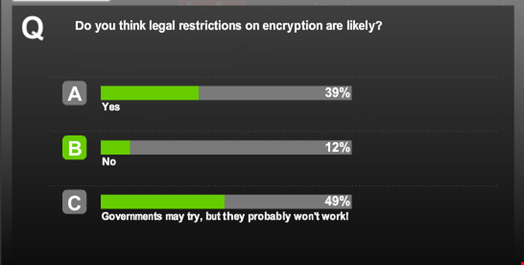

Comments from government officials that encryption should be restricted or banned are misguided and highly unrealistic according to the panel of experienced information security professionals speaking at the Infosecurity webinar, ‘Encryption Under Attack: Government vs Privacy’.

Encryption technologies have recently been targeted by governments and law enforcement, with the US government and Apple squaring off over mobile encryption, and UK prime minister David Cameron generating disbelief with his comments that there should be no means of legal communication that cannot be intercepted and read.

The panelists highlighted this issue as just one facet of the ongoing debate about the extent to which private technology enterprises and governments should share information.

“Extensive information sharing between western companies and western governments has taken place for some time, and not just in areas of national security,” suggested Dave Clemente, senior research analyst at the Information Security Forum. “A significant amount goes on regarding illegal content like child pornography. It’s in areas of national security where the subject becomes more difficult.”

The Snowden revelations about the extent of government surveillance have complicated relations, Clemente added. Tech firms have been encouraged to add encryption to assure customers that their privacy is being protected.

But there are now suggestions that governments should be able to place backdoors in such technologies, to give them complete access to communications that are currently encrypted.

“But if a government can make use of the backdoor, who else can?” cautioned Justin Clarke, chair of the London Chapter of OWASP and head of research at Gotham Digital Science. “Having insecure encryption means there is no trust. You don’t have the confidence in the method.”

“Introducing backdoors is the road to disaster,” concurred Amar Singh, CISO and chair of the UK Security Advisory Group. “If one organization has access, others will.”

Kneejerk Reaction

The backdoors suggestion is not only antithetical to the very idea of security, but it actually wouldn’t aid government particularly well either, panelists suggested.

“Even if you were to listen to a two-way discussion that was encrypted,” said Ben Sewell, ISM/ISO for TUI Group, “there is not necessarily a way to understand that discussion.”

In addition, “Under RIPA,” explained Clarke, “the [UK] government already has the power to demand encryption keys.”

So why is the government even making these suggestions in the first place? “This seems like a kneejerk reaction, because governments are looking for a way for the bad guys not to be able to communicate,” said Sewell, adding that “I don’t think banning the root of that communication is the right way to go about it.”

Indeed, coming as they did in the wake of the Paris shootings, prime minster Cameron’s claims seem particularly cynical, suggested Clemente: “In the UK context, there’s an election coming up, there is plenty of motivation to be seen as tough.”

Lack of Clarity

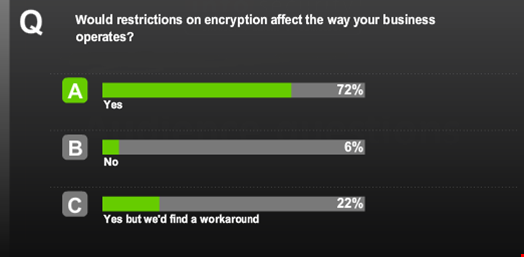

But beyond vague, threatening statements, governments on both sides of the Atlantic have not offered a great deal of clarity on this issue of what banning encryption would really mean, the panel commented. Indeed, there seems to be little comprehension from the authorities about just how fundamentally embedded encryption is in everything we do in the virtual world.

“Encryption is routine,” said Clarke. “It is one of the toolkits we use for identifying who somebody is, that they are correctly authorized to access things – we use it all the time and don’t even realize it.”

“We need to make encryption more user-friendly – those who are adopting the cloud are not finding it easy to enable data encryption"Amar Singh

Sewell commented: “If we didn’t have encryption, things like Paypal wouldn’t exist, or online banking. Fundamentally it’s just not realistic to say that we should ban encryption or not use it. There’s not been enough clarity about what encryption is [in this context]. Is it things like the major encryption protocols? Is it things as simple as random number generation?”

Clarke added that “The word ‘ban’ just seems bonkers. I don’t even see how that can be part of a logical discussion.”

Business Impact

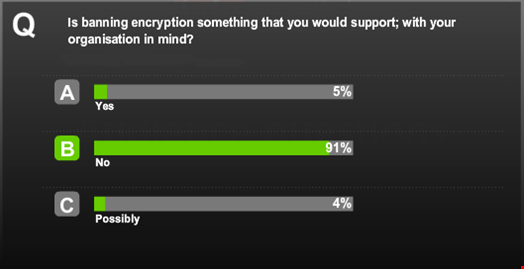

The business impact of a potential ban on encryption in any country would be so far-reaching, the panel pointed out, that no country has yet taken this hardline approach.

“Tapping into encrypted streams of data, not necessarily informing the parties involved – in the business sense this may not give organizations the ability to respond in kind, to go to court to gain injunctive relief or to fight the disclosure of this kind of information,” offered Clarke.

Sewell, meanwhile, cautioned that “The UK deals with many services outside the UK, and cloud services – what does [a ban on encryption] do to our ability as a nation to use things like Salesforce and software as a service? Does that mean, as a UK business, you wouldn’t be able to source that?”

In addition, the costs of fundamentally overhauling the way encryption is deployed to meet a new legal framework would be huge, the panel suggested.

Instead of hostility towards encryption, panelists stressed the need more education of the awareness of the benefits such technologies bring to the individual and enterprises.

“Many organizations still don’t understand encryption,” said Singh. “They are also not using it as they should. They are using the cloud, but the only understanding is that they have SSL. Some CIOs are just using HTTPS, they are not using encryption in any other form. From a consumer point of view I find that worrying.”

“We need to make encryption more user-friendly – those who are adopting the cloud are not finding it easy to enable data encryption. They are not demanding encryption as a default, unless you start telling them, but it becomes a bit onerous as workflows have to change.”

This live webinar was broadcast on 5 February, and is now available on demand.