Hacktivism, once a symbol of digital protest, has undergone a radical transformation and a new evolution is unfolding in the cybercriminal landscape.

Today, some hacktivist groups are turning from defacing websites and leaking documents to a different, more lucrative tactic: ransomware.

While this trend is particularly pronounced among Russian-aligned hacktivists, politically oriented hackers elsewhere also adopt similar strategies.

This shift marks a significant change in the landscape of digital activism, raising questions about the motivations driving these groups and the fine line between protest and profit.

As hacktivists embrace ransomware, the boundaries between activism and cybercrime are becoming more blurred than ever before.

Infosecurity spoke to cyber threat intelligence experts about these tactic shifts and explored the reasons explaining the rapprochement of hacktivists and ransomware groups.

Recent Rise in Hacktivism Activity

Defining Hacktivism

The term hacktivism was first used by writer Jason Sack in a 1995 article about Fresh Kill, a British-American experimental film directed by Shu Lea Cheang.

Now its use in cybersecurity is generally attributed to a member of Cult of the Dead Cow, a Texas-based hacker group, who used it to describe the nature of what they and their peers were doing in a 1996 email.

Since then, hacktivism has broadly been used to describe hacking endeavors that were neither motivated by money nor sponsored by a nation-state – although the interests of hacktivist groups can align with those of a nation-state.

Hacktivist groups typically deploy website defacement and spoofing, disruptive attacks like distributed denial of service (DDoS), destructive attacks and information manipulation campaigns.

Typically, these cyber-attacks are conducted to further the goals of political or social activism.

"While the geopolitical rhetoric escalated, so too did the force and impact of the denial-of-service attacks recently favored by hacktivists."Charl van der Walt, Head of Security Research, Orange Cyberdefense

Charl van der Walt, Orange Cyberdefense’s head of security research, told Infosecurity, “Hacking, crime, espionage, politics, and ideology have long been difficult to tease apart, and hacktivism has always been a central, if somewhat benign, element of this complex mix.”

Geopolitical Tensions Prompt Hacktivism Uptick

The cyber threat intelligence community has observed a rise in self-proclaimed hacktivist activity over the past few years.

Van der Walt attributes this uptick to the war in Ukraine.

“We observed a significant surge in hacktivist activity supporting both sides of the conflict. While the geopolitical rhetoric escalated, so too did the force and impact of the denial-of-service attacks recently favored by hacktivists,” he said.

In one example, the hacker collective Anonymous declared ‘war’ on Russia.

Two hacktivist groups Orange Cyberdefense has been tracking, Anonymous Sudan and Noname057(16), are also directly or indirectly engaged in the tensions surrounding the war in Ukraine.

“Anonymous Sudan has apparently succeeded in creating uncertainty and fear among its targets, especially against Nordic countries. Geopolitical tensions in the region escalated to the point that Sweden and Denmark had to introduce measures to preserve safety, and Sweden raised their terror threat level after encountering heavy international unrest,” Van der Walt added.

Hacktivists Embrace Ransomware

As the war in Ukraine “politicized” cyber threat activity, in Van der Walt’s words, we have seen a flurry of self-proclaimed hacktivist groups emerge, some new and others known in the cybercrime ecosystem.

Several actors previously considered hacktivists started a profit-making business over the same period.

Speaking to Infosecurity, Anastasia Sentsova, a ransomware cybercrime researcher at cyber threat intelligence firm Analyst1, said she has observed an uptick in Russian-aligned “so-called hacktivists” embracing financially motivated cybercrime.

From Hacktivist to Hacktivist-Like Groups

‘Traditional’ hacktivist groups were often considered relatively harmless, but Sentsova said that the dynamics had shifted significantly since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

New groups, which she calls “hacktivist-like” groups, are characterized by their high level of coordination, large membership and activities closely aligned with state interests.

“The probability of government influence (direct or indirect) or support is high, as these groups often pursue specific political or ideological agendas, reflecting a more strategic and state-oriented approach to cyber operations,” she explained.

These groups place themselves at the crossroads between independent hacktivism, profit-making cybercrime and state-sponsored cyber activity.

“Given the substantial resources and support these groups receive, including significant technical and informational backing, they should be considered a high-level threat,” she added.

Observed Cross-Activity Between Ransomware and Hacktivist Groups

Self-proclaimed hacktivist groups’ new interest in the ransomware ecosystem takes many forms, including the six following scenarios:

- Hacktivist groups using publicly available ransomware tools (e.g. leaked LockBit 3.0 builder)

- Hacktivist groups launching their own ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) toolset

- Ransomware groups aligning themselves politically while keeping a ransomware business

- Ransomware groups turning to hacktivist activity

- Direct collaboration between ransomware groups and hacktivists

- Ransomware groups and hacktivists targeting the same victims one after the other

Hacktivists Exploit Ransomware Tools for Disruption

Although not a new phenomenon, the scenario of hacktivists using ransomware tools is probably the most widespread, Jim Walter, a senior threat researcher at SentinelOne, told Infosecurity.

“The tier one groups, made up of script kiddies-level hacktivists, just try to disrupt and cause chaos and mayhem, not necessarily profit in a ransomware operation. On top of the historical defacement and DDoS activity, they now have access to widely available ransomware tools like the LockBit builder to make a statement,” he explained.

In those cases, these groups generally do not collect a ransom.

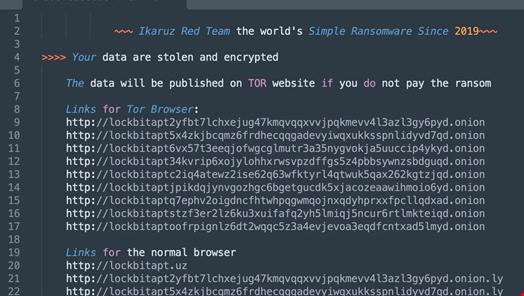

In May 2024, Walter published an analysis of the Ikaruz Red Team, a hacktivist group affiliated with the Turk Hack Team which conducted attacks against Philippine targets. The group used the leaked LockBit builder in its attack but did not try to make a profit.

In June 2024, pro-Ukraine hacktivist group Cyber Anarchy Squad claimed a series of ransomware attacks on Russian networks but did not try to make any profit. Although the group’s toolset remains unknown, it is likely that it used off-the-shelf tools.

NullBulge, a hacktivist group that claimed to have leaked over one terabyte of data from Disney in July 2024, reportedly uses publicly available tools like Async RAT and Xworm before delivering LockBit payloads built using the leaked Lockbit builder.

Rise of Hacktivist-Run Ransomware Services

One of the most recent examples of hacktivist groups launching their own RaaS toolset occurred in June 2024, when KillSec, a well-known Russian-aligned hacktivist group, announced the launch of a RaaS platform.

The same month, AzzaSec, an Italian-based hacktivist group aligned with Russian interests, announced it was launching its own Windows ransomware builder before joining forces with Noname057(16).

Ransomware Groups Turn Political

Ransomware groups turning political has historically proved more challenging, Van der Walt said.

The Conti case offered some insight into this dynamic when a rift occurred in May 2022. At this time, pro-Russia individuals announced the group was aligning itself with the Putin regime, antagonizing other members who supported Ukraine. This resulted in the group being disbanded.

“Some of the individuals involved in these groups are cynically criminal, some are ardently political. Our sense is that some may be just naïve, angry, and delinquent and can thus be expected to act erratically and engage in both crime and activism,” Van der Walt said.

While Conti’s political shift failed, other groups like Snatch and Stormous seemed to juggle with profit-making threat activity and political alignment better.

“Our research into potential collaboration between RansomHouse and/or Dark Angels with Snatch and Stormous based on the analysis of crossclaims suggests that they are engaging in hybrid ransomware/hacktivist-like activities,” wrote Sentsova in her latest report.

Another, GhostSec, embraces several scenarios, constantly slithering between ransomware and hacktivist activity.

In October 2023, this self-described "vigilante" group released a novel type of ransomware, called GhostLocker, before conducting double extortion attacks across multiple countries and business sectors, in collaboration with Stormous.

Ransomware-Hacktivist Collaborations

GhostSec and Stormous further developed their collaboration, deploying a joint RaaS program called StmX|GhostLocker.

Both are now part of a semi-hacktivist, semi-extortion nexus group called ‘The Five Families.’

According to Van der Walt, this collective consists of three hacker groups, a ransomware group and a malware forum that apparently colluded in the hack of the Presidential website of Cuba.

“At least three of these groups appear to have withdrawn or ceased operations since then, however,” the researcher added.

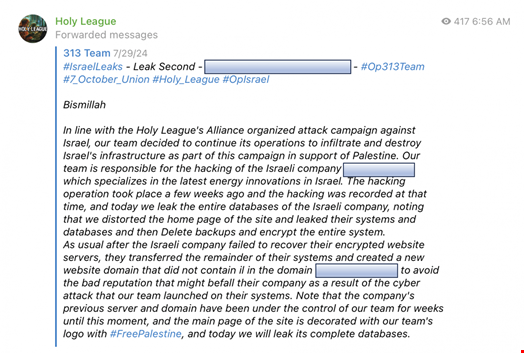

Another such pro-Russia collective is the Holy League, which counts the Cyber Army of Russia, one of the most active hacktivist groups currently, between its ranks but is also involved in ransomware attacks against Israel entities.

Killnet, one of the prime examples of ransomware-hacktivist collaboration, has been operating since late 2021.

This pro-Russia collective, known for producing social media content and collecting donations via Toncoin, a cryptocurrency linked to the Telegram instant messaging app, includes groups like Anonymous Russia, Anonymous Sudan, Infinity Hackers Group, BEAR.IT.ARMY, Akur Group, Passion Group, SARD and National Hackers of Russia.

However, according to Van der Walt, Killnet is an unusual case and should be understood as a hacker collective that shares common objectives with like-minded hacktivist groups.

“They don’t execute many attacks themselves but work through members of their collective,” he explained.

In a recent report, Sentsova noted, “Although Killnet as a brand is still present in the hacktivist scene, it no longer operates at the scale it once did. They have become more of a local Telegram forum-like and informational source, primarily engaging in influence operations and promoting illicit activities.”

Recently, another trend emerged with hacktivist and ransomware groups targeting the same victims.

In its Cy-Xplorer 2024 report, Orange Cyberdefense (OCD) observed a growing trend of revictimization between different threat groups, including hacktivists and ransomware groups.

Since OCD started tracking this trend 2023 was found to be a record year for revictimization, with 200 occurrences that year alone.

This trend could suggest increased collaboration between hacktivist and ransomware groups and/or affiliates, although this remains to be proven.

Sentsova said it is highly likely that some groups targeting the same victims are collaborating.

Reasons for Hacktivists-Ransomware Groups Alliances

Pro-Kremlin Cybercriminals, the New Russian Elite

In her latest report, Sentsova explained that cross-collaboration between several types of Russia-based threat actors illustrates the interconnected nature of Russian cybercrime, with actors sharing the same forums and platforms while pursuing different objectives.

She attributed this interconnection to several factors, including the “collectivist mindset” of certain Russian underground communities.

"Russian cybercriminals defending national interests are elevated as the new elite."Anastasia Sentsova, Ransomware Cybercrime Researcher, Analyst1

In a “Cybercrime Diaries” blog series, Oleg Lypko, cyber threat intelligence analyst at Own, examined the high level of interaction between several Russian underground communities on hacking forums.

He showed that a handful of platforms attract all sorts of malicious actors, from drug dealers and scammers to hacktivists and ransomware groups. All these communities share tips and discuss the best tools on the market.

Sentsova said that the current political climate in Russia has reinforced these bonds, contributing to a more unified and resilient cybercrime network.

Some Russia-based ransomware groups may choose to publicly align with the Russian regime to avoid law enforcement action or even get unofficial protection from the Kremlin.

“We observe a clear trend of increased prosecution of cybercriminals within Russia who conduct attacks against Russian entities, while those defending national interests are rewarded with favorable positions. The former are tracked down while the latter are elevated as the new Russian elite,” she told Infosecurity.

A notable example is the historic international prisoner exchange that occurred on August 1, 2024. In this exchange, Russia secured the release of 16 individuals, including two prominent cybercriminals, Roman Seleznev and Vladislav Klyushin, who were released from custody.

“This exchange, which primarily involved spies convicted of espionage, highlights a new reality where cybercriminals with demonstrated offensive capabilities are elevated alongside traditional spies within Russia. Their return publicly endorses and validates their actions, signaling a broader acceptance of cybercriminals as crucial players in national security,” Sentsova noted.

Funding Hacktivist Campaigns Through Ransomware

Another reason for conducting ransomware campaigns is that hacktivists need to make money, if not to become rich, at least to fund their politically oriented activity.

While they traditionally used fundraising channels like crowdfunding or donation calls, the access to easy-to-use ransomware tools opens new ways to get funds, said SentinelOne’s Walter.

Gaining Attention

Hacktivists and hacktivist-like groups are pivoting to new types of attacks because defacement and DDoS attacks no longer suffice to gain the attention of their victims and the broader public.

“We are seeing a continuous evolution towards ‘cognitive’ attacks, which seek to shape perception through technical activity,” Van der Walt said.

“The impact has less to do with the disruptive effect of the attack or the value of the data or systems that are affected than with the effect they will have on societal perception. Since the impact is powered by the hacktivist’s message, the actor can choose to make a political statement out of any apparently successful attack,” he added.

To get attention, threat actors need to show skills, and ransomware attacks tend to get extensive exposure through threat intelligence reports, media coverage, and social media accounts sharing ransomware groups’ claims and victims’ disclosures.

Conclusion

The lines between hacktivist and ransomware groups have become more blurred than ever before, in large part because hacktivists had to blend into more traditional forms of cybercrime.

As the threat landscape continues to evolve, with new and more sophisticated attacks emerging constantly and motivations shifting, the motivation of hacktivist groups and cybercriminals deploying ransomware is likely to continue to converge.