Two Russian-aligned cyber espionage squads have been conducting a sophisticated spear phishing campaign against Western and Russian civil society entities for two years, according to the Citizen Lab.

In a new report published on August 14, 2024, the University of Toronto's investigative research group shared that Coldriver, a notorious hacking group backed by Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB), was behind the campaign.

The targets include prominent Russian opposition figures in exile, media organization funders and staff at US and European NGOs.

The activity was conducted alongside Coldwastrel, a newly discovered group. While Citizen Lab acknowledges Coldwastrel’s targeting “aligns with the interests of the Russian government,” the research group did not formally attribute the new threat actor to any country.

Decoding the River of Phish Campaign

The spear phishing campaign, dubbed River of Phish, was uncovered after a month-long investigation by Citizen Lab researchers in collaboration with Access Now, a digital rights advocacy non-profit, as well as other civil society organizations.

It started in 2022, coinciding with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The hackers’ typical approach involves an email exchange with the target during which the sender impersonates someone known to them and requests them to review a document relevant to their work, such as a grant proposal or an article draft.

The email message usually contains a lure as an attached PDF file purporting to be encrypted or ‘protected,’ using a privacy-focused online service such as ProtonDrive, for example.

If the target clicks on the link, their browser will fetch JavaScript code from the attacker’s Hostinger server that computes a fingerprint of the target’s system and submits it to the server. The target will then be redirected to a webpage crafted by the attacker to look like a genuine login page for the target’s email service (e.g. Gmail or ProtonMail).

If the target enters their password and two-factor authentication (2FA) code into the form, these items will be sent to the attacker, who will use them to complete the login and obtain a session cookie for the target’s account.

“This cookie allows the attacker to access the target’s email account as if they were the target themselves. The attacker can continue to use this token for some time without re-authenticating,” the Citizen Lab researchers noted.

The report also mentions additional techniques to make the whole process seem legitimate and avoid detection, such as intentionally omitting the attached PDF in an email or pre-populating the fake email login page with the target’s email address.

The use of Hostinger domains, which are typically hosted on shared servers that rotate IP addresses approximately every 24 hours, makes the campaign more challenging to track.

Coldriver, A Long-Standing FSB-Backed Threat Actor

This campaign aligns with previous activity from Coldriver.

Also known as Star Blizzard, (Blue) Callisto, and Blue Charlie, Coldriver is a Russia-based cyber-espionage group believed to be linked to the FSB’s Centre 18.

Citizen Lab said the group has been active since at least 2019. Some cybersecurity firms, including F-Secure, believe the group was active as early as 2017 or even 2015.

It is known to focus on credential phishing campaigns targeting high-profile NGOs, former intelligence and military officers and NATO governments for espionage purposes.

Citizen Lab has attributed the River of Phish campaign to Coldriver after comparing its investigation results with materials from Microsoft Security Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC), Proofpoint, and PwC, among others.

Coldwastrel, A New Russian-Aligned Hacking Group

Additionally, the Citizen Lab researchers concluded that a cyber-espionage group distinct from Coldriver also participated in the River of Phish campaign.

This threat actor, whom Citizen Lab named Coldwastrel, was notably behind emails sent to Access Now staff members since March 2023.

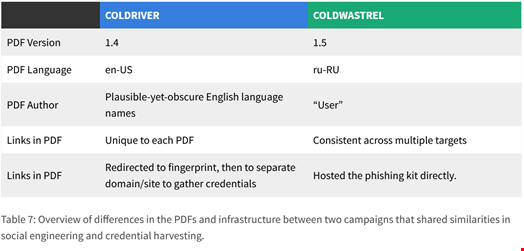

Although this group’s tactics were similar to Coldriver’s, the researchers found numerous differences.

These include the PDF version and language used in the phishing campaign as well as differences in the operating infrastructure.