By 2020 we are going to have a skills shortage of 1.8 million, so you keep hearing. What does that actually mean? The scary answer is we don’t know. However, we can guess.

In 2017 it was estimated that 46% of UK organizations had suffered a cybersecurity incident, with impacts ranging from financial loss to permanent corruption of data. In 2020, the skills shortage will have worsened, meaning that it will be harder to prevent (or respond and recover from) cybersecurity incidents such as these.

That’s also assuming that the threat landscape doesn’t change: if threat actors and their exploits continue to significantly increase in maturity and the targets become even more lucrative, we can be assured that the cost to the world and UK economies will be even greater than it is today.

The success of previous initiatives to address cybersecurity skills gap indicate that the potential success of UK initiatives (focused mainly on education in schools and universities) may be fruitless. For the last ten years, the US government has been sponsoring education programs to facilitate their growth of cyber skills that can be applied to the market. However, the US still has an estimated current shortage of 30,000 jobs, indicating that education and awareness programs alone are not addressing the shortage quickly enough.

Surely, there’s a requirement for organizations to also play their part in addressing the skills gap?

So what is the cyber skills shortage?

The information security skills shortage is the deficit of skilled cybersecurity people to fill required cybersecurity roles. To clarify, it is two things:

- A lack of people working in and entering the cybersecurity industry (this gets talked about A LOT)

- The people who are currently in the industry lack the required skills to perform roles effectively (this is generally forgotten about when we talk about the cybersecurity skills shortage)

Without skilled people it is unlikely organizations can effectively assess, plan for, protect, respond to and recover from cybersecurity threats and incidents.

As an industry, we are bad at communicating that cybersecurity spans lots of areas and that it is not just a bunch of technical roles. In fact, lots of cybersecurity roles have a business facet and although they require an understanding of cybersecurity concepts, the required skills are similar to those used in roles found quite easily throughout any business.

This is not denying the need for technical skills: there are plenty of niche technical roles whose market is significantly smaller (key examples being ethical hackers, forensic experts and reverse malware engineers). However, there is a key risk of organizations not understanding if these roles are required in the first place.

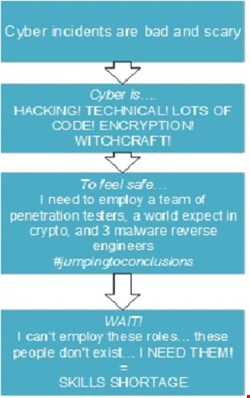

Initially, organizations should be confirming their cybersecurity strategy, ideally focused on reducing risk and aligned to that of their business. The subsequent recruitment activity should be identifying key gaps in capabilities to realize that strategy, followed by finally opening roles as appropriate. This sounds simple but there is a danger the following is currently happening:

How do we recruit for cybersecurity roles?

As highlighted, firstly there’s a danger that organizations are not appropriately identifying gaps and their required roles which will help them achieve their strategy. There’s a relevant example of how organizations should be doing this: developed by NIST as part of the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework (NCWF).

Additionally, organizations need to ensure that the roles agreed identify the appropriate (and sensible) skills required to perform them. As part of my MSc project at Royal Holloway, I spent my summer analyzing job descriptions for cyber roles at UK organizations and mapping them to the skills required for the applicable role defined in the NCWF. The main findings included:

- Cybersecurity role descriptions are not aligned to best practice frameworks. Organizations are not articulating all the skills required to perform roles according to best practice frameworks, putting them at risk of making inadequate hiring decisions. In other words, resources hired for these roles may not be able to perform the entire skillset needed to fulfil that role. Additionally, organizations may not correctly identify skills gaps for appropriate training and development.

- There is an emphasis on excess skills. There were plentiful examples of roles which described a long list of skills required (‘must be and pen tester…. and a firewall expert…and an incident responder….AND a secure application developer’). Upon analysis of best practice frameworks, these ‘excess skills’ were aligned to quite different roles and not required for the advertised role. Surely, there’s a chance this misconception about requirements for roles is causing difficulties recruiting for cyber roles?

- There is an emphasis on certifications and years of experience. This again reduces the pool of talent eligible to apply and be considered for those roles. There is no certainty that candidates with certifications are more skilled than those without – one candidate may have valuable experience in the industry and excellent skills but no qualifications/certifications, yet another may have no experience but a CISSP certification; if screening based on job specification, only the candidate with the CISSP would be considered.

What are the solutions?

Organizations are not currently identifying and articulating the appropriate skills for cyber roles. This undoubtedly has unwanted impacts on the ability for organizations to recruit into their cybersecurity functions and therefore, increases the perceived scale of the cybersecurity skills gap because they are not able to fill their open roles.

If there is a chance that organizations are facilitating the extent of the skills shortage, they must have a responsibility for helping to close it. The good news is there are some ideas about how to tackle it. After identifying the concerning trends in cyber recruitment, I consulted key industry players to understand how organizations might help tackle the shortage. Some of the proposed solutions are self-explanatory and have been explored before:

- Select the location of roles to be near current and upcoming talent pools for cybersecurity skills.

- Implement improved governance of the cybersecurity recruitment process, so that security functions are involved at all stages of reviewing potential candidates.

Other proposed solutions cover the following:

- Define and understand cybersecurity strategy to better assess and identify skill gaps specific to organizations.

- Apply good practice skills frameworks (such as the NIST NICE framework) to identify and define the appropriate skills required for cybersecurity roles in organizations.

- Utilize more transferable skill-sets either within or outside of the organization. Cybersecurity is a business issue and spans all functions; organizations should be looking to embed security into current roles e.g. supplier security as part of due diligence in procurement. Additionally, recognize what skills are transferable and what can be taught with adequate training – we have a responsibility to build a workforce.

- Invest in cybersecurity training to facilitate the development of skills and reduce the reliance on recruiting the ‘perfect candidate’. There is an opportunity for organizations to sponsor a conversion course which would support a rise in the number of security professionals and the ability to enter the industry at different points in a career path (rather than relying on organic growth from school/university).

Of course, it is unlikely that these proposed solutions alone will solve the skills crisis in our industry. However, it is clear that organizations are required to step up and improve the situation under their influence. This approach along with government initiatives across education and awareness may significantly reduce the estimated 1.8million deficit by 2020.