Security compliance is fundamental to any cloud offering today, with a myriad of security compliance frameworks that need to be complied with for organizations to offer cloud-based services in various geographies. A ‘move to cloud’ introduces a paradigm shift for organizations offering cloud services around their people, processes, technologies and documentation, all of which must now align to a cloud-based ecosystem. The challenge is particularly acute when government agencies are the customers, given the need for strict adherence to various regulatory frameworks. As a result, organizations often invest disproportionate resources and time in trying to comply with security compliance requirements. Whether this investment guarantees higher levels of security or only checks boxes of a framework that has inherent flexibility in how it can be implemented is an open question.

Security compliance requirements can be vague in their definition and need constant evaluation

Several countries today have some form of security compliance framework for cloud service providers (CSPs) to align with for government agencies to consume their services. The US has FedRamp, which focuses solely on cybersecurity by aligning with the NIST 800-53 standards. The UK has a similar framework in the form of G-Cloud 12, while the EU’s ENISA has several guides on securing GovClouds for CSPs.

These framework requirements can range widely in terms of categorization, such as technical, operational, management or documentation controls. They are also often vaguely worded even when they are technical in nature, leaving sufficient flexibility for the CSPs to determine their own implementation choices. In addition, periodic testing or continuous monitoring activities around scanning, testing and remediation plans are needed to maintain compliance.

Checking the box approach to security compliance can still leave CSPs vulnerable to security threats

Given the ambiguity built to control the verbiage of various frameworks, implementation guidance is often left to the CSPs to ultimately decide on. For example, the FedRamp control numbered SC-8 talks about protecting transmitted information, requiring CSPs to use from the list of approved cryptographic modules (FIPS 140-2). This fairly broad list is arranged in different security levels without being prescriptive. The algorithms that the organizations choose will eventually determine how secure their data in transit is.

Also, organizations tend to focus on stronger controls only for federal customers while not focusing on their commercial offerings as much in terms of security. But given that most companies use a common continuous integration/continuous delivery (CI/CD) pipeline and infrastructure-as-a-code (IaC) tools, it would not be surprising if a lot of control deficiencies creep into federal environments. For instance, a major identity management company had a significant breach in 2022 and had to come out with a statement reporting that their federal customers had not been impacted.

Risk should drive the stringency of control implementations, not just a compliance checklist

A lot of redundant processes, time and effort needed to stand up federally certified cloud environments can be addressed by introducing a risk-based decision-making process. Many organizations lack the methods to accurately determine risk. Infrastructure, code and application-level risk assessments can be conducted to determine the inherent risk for each component and the residual risk upon the implementation of controls. This helps not just in an optimal implementation of a control but in selecting what controls are most applicable.

Risk assessments could include discovery questions, impact analysis, likelihood analysis, threat modeling and other activities that ultimately provide the risk scores. Based on such scores, organizations can determine their risk appetite. This could lead organizations to do more in control implementations instead of just the minimum needed to comply.

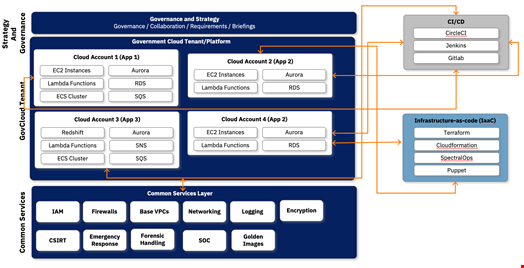

Additionally, organizations can invest in architectural frameworks that don’t necessarily choose to separate their commercial and federal offerings in terms of stringency of controls, but unify them so that every cloud offering is secured to the same level. A best practice can be to offer an entire range of federally compliant and risk-based common services to various teams supporting different functions and applications such as IAM, networking and so on, and a common set of IaC tools and CI/CD pipeline, all with an overarching layer of governance to support it. This offers a common framework for all teams wanting to develop applications to support either government or commercial clients, because a whole host of capabilities are addressed as a common layer, and are already compliant with federal requirements and hardened based on risk.

Additionally, organizations can invest in architectural frameworks that don’t necessarily choose to separate their commercial and federal offerings in terms of stringency of controls, but unify them so that every cloud offering is secured to the same level. A best practice can be to offer an entire range of federally compliant and risk-based common services to various teams supporting different functions and applications such as IAM, networking and so on, and a common set of IaC tools and CI/CD pipeline, all with an overarching layer of governance to support it. This offers a common framework for all teams wanting to develop applications to support either government or commercial clients, because a whole host of capabilities are addressed as a common layer, and are already compliant with federal requirements and hardened based on risk.