In the wake of 9/11, American intelligence services saw that inter-agency barriers had prevented analysts from finding connections between different sources of information. As a result, they missed clues that might have helped prevent 9/11 or other terrorist attacks.

These barriers were partly political, but secrecy regulations were also among the reasons for closing access to the information. Realizing this, the State Department, the military, and intelligence agencies started sharing data much more freely across agency boundaries.

But now, after the leak of a quarter of a million State Department documents – not by a State Department staffer, but by an Army enlisted man – we can expect the American government to ratchet up the controls, to limit access across agencies, to close documents to any but those with high clearance levels.

But there is no way back, no way to stem the flood. Information flow is too essential to the workings of modern intelligence analysis.

The same is true across many industries. Just as security analysts learn about terror plots by connecting the dots in intelligence data, epidemiologists identify the spread of unknown new diseases by finding reports of symptoms in different places, and market analysts track hidden trends across sales and other data.

Knowledge workers used to carry out well-defined routine processes, but such activities are now computerized or offshored. In the twenty-first century, knowledge workers are increasingly using their abilities to discover patterns where none were known; to find connections across disparate sources of data; or to identify suspicious behavior on the basis of anomalies in the data streams. They need full access to information from a variety of sources, from within their organization and from others as well. But this very openness increases the risk of exposing sensitive data about the organization or its customers.

| "People who live in glass houses should put up some window shades" |

Unfettered access to data gives tremendous power. The web has shut down any doubts about this claim, as today’s casual web users can do things that well-funded analysts couldn’t do 15 years ago. Anyone can use a search engine to find what they need, across the billions of web pages exposed by millions of sources. In the last decade, this sort of flexible, accessible data gathering has become so easy that people take it for granted in their private life. But ironically, at work, where analyzing data is all-the-more important, the same people find that they cannot flexibly access the masses of information in enterprise systems.

The pressure to give the intranet the openness of the internet is so great that organizations are giving their employees access across information silos, with the concomitant risks of leakage and privacy violations.

Even those organizations that resist these pressures find that they have to open up, because of new regulations. HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, requires health organizations to let information flow across boundaries, but also requires them to the preserve patients’ privacy. The Freedom of Information Act, better known as FOIA, requires government agencies to release their documents, allowing citizen activists and journalists to discover hidden connections between them, but the same law also requires removal of personal or national security information.

Protecting structured data is relatively easy, because databases and application frameworks feature role-based fine-grained access control systems. Documents, however, contain a mixture of information types. Simply allowing or blocking access to a document does not promote the flexible browsing of information that knowledge workers need.

When it comes to the leakage of sensitive information within documents, I contend that people who live in glass houses should put up some window shades. The solution is to let authorized users browse documents in a web-based viewer that redacts sensitive parts of the text, following a role-based policy. Automated systems find personal names, social security numbers, and other types of information as specified by the regulations, and delete them from the document as it is displayed.

For example, doctors tracking the spread of an epidemic in their hospital should be allowed to review medical documents for all patients, even those they are not treating – but without any text that personally identifies the patient. A junior analyst might need to see enough of an intelligence document to route it to the senior specialist in a given area, but without top-secret identification numbers.

Redaction is essential to free data flow, but it is not enough. Defined policies always risk deleting too much or too little, removing essential information or revealing what shouldn’t be. However, if authorized users can ask to securely fill in some of the blanks, after stating their reason for doing so, then the redaction policy can be strict, yet still allow the users the flexibility they need. (Of course, many highly sensitive types of data will remain redacted and irretrievable, depending on the policy and the role of the user.)

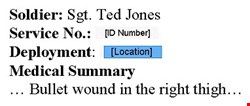

Using a system that allows each user to see certain text elements, but only when they have a valid purpose, a military doctor might call up an injured soldier’s medical report. The doctor sees the medical information, but the location of the soldier's last deployment is redacted (see Figure 1).

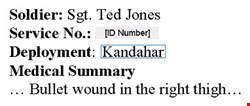

Although the doctor has security clearance, there is no need to display potentially top-secret non-medical data on every access to a medical document. If the doctor suspects an exotic disease and needs to see the redacted text, then they can click on the redacted area, input the reason, and the text will then be retrieved from the server and securely filled in (see Figure 2).

Because the users in question is already cleared and authenticated, and their every access to a unit of text is logged, they will take care in accessing such data only as needed.

Too much openness, as well as too little, both pose risks. Document viewing with automated redaction is one part of the balance. Allowing authorized users to retrieve the redacted information is another.

David Brin, in his 1998 book The Transparent Society, identified a trend toward greater openness, toward a free flow of data that sometimes endangers government secrecy and personal privacy. We are all learning to live in glass houses. We can’t change that, but we should install some window shades – and then roll them down or pull them up as needed.

Dr. Joshua Fox works in the area of privacy protection software. He served as chief architect at Unicorn Solutions (acquired by IBM), where he participated in the development of the industry-leading enterprise semantics platform; later, he was principal architect and director at Mercury Interactive (acquired by HP), where he guided cross-company product integration. In his current position at IBM, Fox co-founded the Optim Data Redaction product and now manages its development. He frequently speaks at business and technical conferences and writes for journals on information management and enterprise architecture. Links to his talks and articles are available online.