The evolving landscape of cybersecurity risks means different responsibilities and roles for boards – especially in light of the new SEC reporting rules.

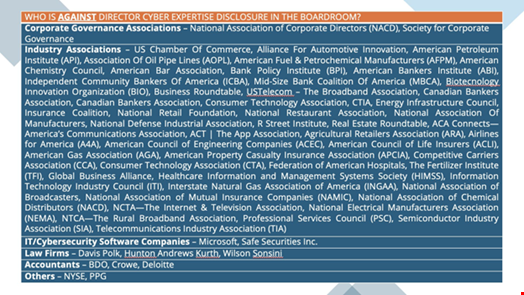

Pushback from numerous parties is commonplace, yet real-world data and scholarship show that a lack of cybersecurity expertise among board members hinders proper understanding and prioritization of cybersecurity risks.

Cybersecurity suffers from large-scale misalignments in top-down and bottom-up coordination, prioritization and resourcing. The effects of such misalignments are manifold, with cybercriminals deftly exploiting gaps and seams to squeeze out data and dollars, now estimated at trillions of dollars per year.

While many corporate boards are gaining familiarity about cyber risks and strategies, through table-top incident response exercises, off-sites and information sharing, dilemmas on cyber reporting and board expertise remain.

Further, standard playbooks for incident response are still not well established and a sad pattern emerges: post breach, companies often scramble to remove C-suite executives and bring in external consultants to review suboptimal practices.

Often, these efforts rely on lawyers whose counsel may preserve confidentiality or protect brand and leadership, but may also undermine desperately needed broad gains in cybersecurity.

Impact of SEC Rules

Ultimately, the SEC’s rules do not force the requirement of cyber expertise on boards, but the four-day rule for material determination and reporting – which many entities also lobbied against – puts clear onus on boards to mainstream cybersecurity as part of their overall risk management program.

Furthermore, public companies are now required to annually detail in their Form 10-K how the board oversees risks related to cybersecurity threats, as well as the role of management in evaluating and handling material risks.

While there is a critical need for more than symbolic board prioritization of cybersecurity risks, gaps remain in explaining threats and the return on investment to the C-suite. Too often, executives are treated to complex technical jargon or litigious verbiage when plain business language is needed most.

To date, much of the pushback from boards against cyber expertise requirements has fallen into one of the five fallacies, first detailed by Bob Zukis, CEO of the Digital Directors Network.

- One Size Fits All. False claim that the SEC proposed rule defines and dictates one approach for all companies on what constitutes a director with cybersecurity expertise

- One Trick Pony. Incorrect view that CISO’s have too narrow of a competency profile and skill set to contribute to the broader boardroom agenda

- Scarcity. Claim that the generally hyped cybersecurity skills shortage means there also aren’t enough cyber experts to go around in the boardroom

- Slippery Slope. Evidence free claim that director cybersecurity expertise disclosure or presence on the board will create negative and unintended consequences elsewhere

- Outside Expert. Mistaken belief that outside experts or management expertise is a suitable replacement for corporate governance that fails to recognize the purpose of corporate governance and the fact that fiduciary duties cannot be delegated

Nonetheless, the trend towards board responsibility for cybersecurity is clear. For example, Part 500 of Title 23 of the New York Codes, Rules and Regulations (NYCRR), often referred to as the New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) Cybersecurity Regulation, which covers banking, insurance, and other entities operating in New York, requires board’s being informed on cybersecurity.

CISOs must report in writing at least annually to the covered entity’s board of directors or equivalent governing body, including information on the overall effectiveness of the cybersecurity program and the material cybersecurity risks associated with the entity.

In the meantime, significant cyber-attacks against critical infrastructure have increased. With the preponderance of critical infrastructure in private hands, the private control of critical infrastructure presents further challenges for transparency and accountability. Presently, a complex web of interlocking and, at times, overlapping regulations forms the basis of US requirements.

At the Federal level, in 2022 the Biden Administration signed CIRCIA into law. While the law primarily deals with reporting requirements and does not explicitly mandate board understanding or oversight of cyber risk, it indirectly encourages higher levels of corporate governance regarding cybersecurity. Equally, the 2023 update of the widely used NIST Cybersecurity Framework, which was also many years in the making, puts the issues in stark relief by including a new Govern function.

Active Government Involvement

The government's active involvement in investigations and support helps, too. For example, the 2013 Target hack or more recently efforts from the Department of Health and Human Services to assist patients and providers after the costly Change Healthcare breach suggests hope for improved risk management amidst escalating cybersecurity threats, particularly against healthcare providers.

Public-private partnerships are set to offer some relief here: in June 2024, the White House announced an initiative with the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the National Rural Health Association, Microsoft and Google, to begin offering cybersecurity services to rural hospitals across the United States.

Security training, risk assessments, and critical updates will go far. However, private entities must also prioritize cybersecurity measures to prevent breaches and protect critical infrastructure. Too often the basics are left undone or insufficiently resourced, with leadership consigning cyber to a Black Swan event or, perhaps worse, unable to commit scarce resources.

Key Recommendations for Boards

When leaders prioritize transparency, actively engage in risk discussions and allocate adequate resources to risk management initiatives, they send a clear message that managing risk is possible. The tone set by the top echelons of an organization is the cornerstone for understanding risk.

Empirical evidence indicates that cybersecurity should be a board-level priority, and companies need people and structures that allow for direct communication and relationship-building between the board and the cybersecurity organization.

To further improve cybersecurity, boards should establish a separate committee that focuses solely on risk management. This committee should have a direct relationship with the cybersecurity teams to better advocate for cybersecurity practices to the rest of the board, especially if the CEO is not providing adequate advocacy. While this breaks boundaries as staff are not typically allowed to interact with board members, the importance of cybersecurity as part of risk management requires careful management.

Cybersecurity is an ever-present risk that companies cannot ignore, and boards must prioritize measures not simply to prevent breaches but to protect the entire organization from harm. Effective oversight is the foundation for strategic decision-making, safeguarding organizational integrity and driving sustainable success. Only then can companies make informed decisions that prioritize risk management, protect crown jewels and become resilient by staying operational in times of adversity.

This article is the second in a two-part series on managing enterprise risk, with the first article focusing on the role of leadership