Every day hackers are being equipped for their next attack, as more and more users are trusting organizations with their personal information online. But with zero knowledge, hackers can be rendered powerless, says Steve Watts

Each day the world’s most popular brands face fresh challenges to protect their uses and customers as they build their online profiles. But a staggering 70% of UK internet users are happy to give away their personal details according to Ofcom. This equips hackers with the knowledge they need to carry out their next devastating attack.

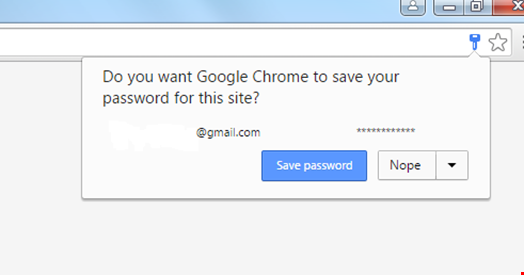

There is one obvious but entirely preventable threat, often overlooked: browsers caching login credentials and simply assuming the same person is online every time. If a business leaves its systems as open as this, a successful attack will lead to dire consequences.

By allowing browsers to cache credentials, users’ personal information is known not only by the system they are logging into, but also by the browser that processes the login request. The same principle can be applied to a range of security systems and this knowledge is power to hackers, as successful attacks have the potential to fully compromise companies.

What would happen if a security system had zero knowledge of the login credentials? Hackers are capable of the most complicated attacks without any help, so it is now time to stop giving them the code to the safe once they have broken in through the front door.

Two-factor authentication (2FA) ensures these credentials cannot work alone to access important information. However, getting this technology wrong is not worth contemplating.

Deployed and used correctly, 2FA is the layer needed to protect digital identity. Yet despite this, users can be left with a false sense of security, as some systems they are logging into request their credentials only during the first time of use. The user only needs to fully authenticate once and they can come back to the system day after day with instant access. For example, an online retailer will ask customers to use 2FA to confirm their purchase but then allow them to return without asking for login credentials.

While private users may deem this to be safe, it is essential for the more security conscious to ensure credentials are physically entered every time a user logs in. Certainly for anyone who has been compromised before, this added protection is absolutely no issue compared to the problems that follow an identity theft.

In 2011 RSA Security had to replace 40 million of its SecurID tokens – nearly every one in existence at the time – after hackers attacked contractor Lockheed Martin. Users logged in with a username and password, with a random number on their token as the second factor to authenticate. This number changed every 30 to 60 seconds, controlled by an RSA algorithm. The hackers attained this algorithm, making the tokens worthless, and putting the entire system in jeopardy.

Automatically separating the records is a secure solution to such a breach. This is where one part is created locally on the customer’s server, while the second is generated using specific characteristics of the mobile device that make it unique, e.g. information about the SIM card, the CPU or equivalent.

"Added protection is absolutely no issue compared to the problems that follow an identity theft"

When the app generates a passcode, the end device decrypts the first half of the seed record and derives the second half accordingly.

Since one part is never located on the employee’s mobile device, the security software excludes the possibility that attacking malware can steal this seed record. Since the seed record is derived in part from the phone’s own hardware fingerprint at time of enrolling, the security system clearly can’t have a copy of the seed. Splitting the seed record means no party has a 360-degree view of the credentials.

As the need for more online security increases, so does the user’s willingness to provide personal and important information. Sharing this knowledge has given hackers access to more information than ever before, allowing them to capitalize on previously trusted systems. To ensure security, firms need to embrace solutions that remove this knowledge completely, rendering the hacker powerless. After all, as Einstein said, “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.”