Failure, not surprisingly, gets a bad rap. Yet, learning from failure is often the quickest path to growth. Take young children learning to walk for example: children will fail many times before getting it right, but at what point do we tell kids to stop? We don’t. We teach them instead to learn and adjust rather than chastise them for falling. In other words, until we know something doesn’t work, we can’t make corrections. This is true in life, business and phishing defense.

(Temporary) failure helps to fight phishing

Learning from mistakes is vital to a strong anti-phishing program. A program must strategically allow for failure before a threat actor attacks. By exposing users to a learning environment where it is safe to fail, companies empower users to strengthen its security infrastructure.

This method works by crafting realistic simulated phishing emails, which clients send to employees—after they’ve explained the program and its educational purposes. The idea is to condition people to recognize and report suspicious emails, so the security team can examine them and, if they’re malicious, respond.

This also helps to take advantage of the “wisdom of the crowd.” That is, the more broadly the simulation engages users in the fail forward process, the more likely one of them will correctly identify and report the next threat.

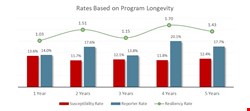

According to our recent report, such an approach pays off in two ways. Firstly through reduction in phishing susceptibility over time and second, through increases in resiliency to all kinds of phishing attacks.

The tendency to fall for a phishing email, or susceptibility, is best addressed through repeated phishing simulations. Research demonstrates that companies using simulation training reduced their susceptibility rate year over year.

It’s okay to raise the difficulty factor. Simulations should progress over time to challenge employees and keep them aware of the latest phishing tactics. After learning to identify basic attacks by failing first, people who reach a level of competence should be ready to fail again when they face complex or unfamiliar phishes.

Example: one business had reduced organizational susceptibility across 4,500 employees in multiple countries to just above five percent. Employees could recognize standard phishing emails, but it was time to raise the bar. The business adopted a phishing simulation program targeted by department, which brought some departments to over 40% susceptibility. Success! No pain, no gain.

The chart below shows that programs improved resiliency even as they got harder, using targeted attacks, personalization and other phishing tricks.

Tougher simulations may cause resiliency to dip, but it rebounds over time as repetition sharpens learning. Fail, succeed, fail again, succeed. What else drives up resiliency? More frequent simulations, rather than one or two a year. When employees get in the habit of reporting possible phishes, they stop playing reactive defense and proactively go on offense.

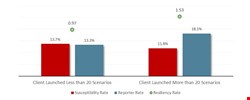

The chart below reflects a steady analysis of simulation failures, including those modeled on malicious emails that made it past the perimeter. In other words, each failure is reintroduced into the program to increase recognition and reporting.

A few more findings from the report shows the power of learning through failure. Resiliency improved in seven out of eight industries, from government to financial services, manufacturing and more. The lone exception was education, which has lower security budgets and lots of BYOD.

Also, resiliency rates went up against all types of phishing, including attachment attacks, click-only attacks and data-entry attacks. In particular, resiliency against OfficeMacro threats rose substantially. Ditto for resiliency to business email compromise (BEC) threats.

Change culture by changing behavior

It’s important to note that positive change won’t happen without positive feedback— employees shouldn’t feel tricked or berated in simulations. With every failure and correction, make sure to add an encouraging word. And again, before launching a simulation program IT leaders need to explain it to employees, whose earnest participation is going to make or break it.

Ultimately, the idea is to drive cultural change, turning a weakness into a strength through individual growth. Failing forward lets employees get ahead of malicious actors and learn what they don’t know in a safe and controlled way.